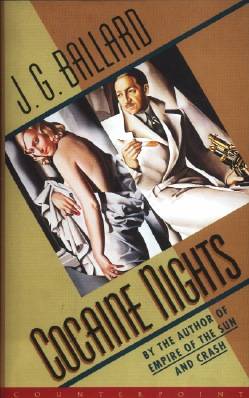

J.G. Ballard

Cocaine Nights

1 Frontiers and Fatalities

Crossing frontiers is my profession. Those strips of no-man's land between the checkpoints always seem such zones of promise, rich with the possibilities of new lives, new scents and affections. At the same time they set off a reflex of unease chat I have never been able to repress. As the customs officials rummage through my suitcases I sense them trying to unpack my mind and reveal a contraband of forbidden dreams and memories. And even then there are the special pleasures of being exposed, which may well have made me a professional tourist. I earn my living as a travel writer, but I accept that this is little more than a masquerade. My real luggage is rarely locked, its catches eager to be sprung.

Gibraltar was no exception, though this time there was a real basis for my feelings of guilt. I had arrived on the morning flight from Heathrow, making my first landing on the military runway that served this last outpost of the British Empire. I had always avoided Gibraltar, with its vague air of a provincial England left out too long in the sun. But my reporter's ears and eyes soon took over, and for an hour I explored the narrow streets with their quaint tea-rooms, camera shops and policemen disguised as London bobbies.

Gilbratar, like the Costa del Sol, was off my beat. I prefer the long-haul flights to Jakarta and Papeete, those hours of club-class air-time that still give me the sense of having a real destination, the great undying illusion of air travel. In fact we sit in a small cinema, watching films as blurred as our hopes of discovering somewhere new. We arrive at an airport identical to the one we left, with the same car-rental agencies and hotel rooms with their adult movie channels and deodorized bathrooms, side-chapels of that lay religion, mass tourism. There are the same bored bar-girls waiting in the restaurant vestibules who later giggle as they play solitaire with our credit cards, tolerant eyes exploring those Unes of fatigue in our faces that have nothing to do with age or tiredness.

Gibraltar, though, soon surprised me. The sometime garrison post and naval base was a frontier town, a Macao or Juarez that had decided to make the most of the late twentieth century. At first sight it resembled a seaside resort transported from a stony bay in Cornwall and erected beside the gatepost of the Mediterranean, but its real business clearly had nothing to do with peace, order and the regulation of Her Majesty's waves.

Like any frontier town Gibraltar 's main activity, I suspected, was smuggling. As I counted the stores crammed with cut-price video-recorders, and scanned the nameplates of the fringe banks that gleamed in the darkened doorways, I guessed that the economy and civic pride of this geo-political relic were devoted to rooking the Spanish state, to money-laundering and the smuggling of untaxed perfumes and pharmaceuticals.

The Rock was far larger than I expected, sticking up like a thumb, the local sign of the cuckold, in the face of Spain. The raunchy bars had a potent charm, like the speedboats in the harbour, their powerful engines cooling after the latest highspeed run from Morocco. As they rode at anchor I thought of my brother Frank and the family crisis that had brought me to Spain. If the magistrates in Marbella failed to acquit Frank, but released him on bail, one of these sea-skimming craft might rescue him from the medieval constraints of the Spanish legal system.

Later that afternoon I would meet Frank and his lawyer in Marbella, a forty-minute drive up the coast. But when I collected my car from the rental office near the airport I found that an immense traffic jam had closed the border crossing. Hundreds of cars and buses waited in a gritty haze of engine exhaust, while teenaged girls grizzled and their grandmothers shouted at the Spanish soldiers. Ignoring the impatient horns, the Guardia Civil were checking every screw and rivet, officiously searching suitcases and supermarket cartons, peering under bonnets and spare wheels.

'I need to be in Marbella by five,' I told the rental office manager, who was gazing at the stalled vehicles with the serenity of a man about to lease his last car before collecting his pension. 'This traffic jam has a permanent look about it.'

'Calm yourself, Mr Prentice. It can clear at any time, when the Guardia realize how bored they are.'

'All these regulations…' I shook my head over the rental agreement. 'Spare bulbs, first-aid kit, fire extinguisher? This Renault is better equipped than the plane that flew me here.'

'You should blame Cadiz. The new Civil Governor is obsessed with La Linea. His workfare schemes are unpopular with the people there.'

'Too bad. So there's a lot of unemployment?'

'Not exactly. Rather too much employment, but of the wrong kind.'

'The smuggling kind? A few cigarettes and camcorders?'

'Not so few. Everyone at La Linea is very happy – they hope that Gibraltar will remain British for ever.'

I had begun to think about Frank, who remained British but in a Spanish cell. As I joined the line of waiting cars I remembered our childhood in Saudi Arabia twenty years earlier, and the arbitrary traffic checks carried out by the religious police in the weeks before Christmas. Not only was the smallest drop of festive alcohol the target of their silky hands, but even a single sheet of seasonal wrapping paper with its sinister emblems of Yule logs, holly and ivy. Frank and I would sit in the back of our father's Chevrolet, clutching the train sets that would be wrapped only minutes before we opened them, while he argued with the police in his sarcastic professorial Arabic, unsettling our nervous mother.

Smuggling was one activity we had practised from an early age. The older boys at the English school in Riyadh talked among themselves about an intriguing netherworld of bootleg videos, drugs and illicit sex. Later, when we returned to England after our mother's death, I realized that these small conspiracies had kept the British expats together and given them their sense of community. Without the liaisons and contraband runs our mother would have lost her slipping hold on the world long before the tragic afternoon when she climbed to the roof of the British Institute and made her brief flight to the only safety she could find.

At last the traffic had begun to move, lurching forward in a noisy rush. But the mud-stained van in front of me was still detained by the Guardia Civil. A soldier opened the rear doors and hunted through cardboard cartons filled with plastic dolls. His heavy hands fumbled among the pinkly naked bodies, watched by hundreds of rocking blue eyes.

Irritated by the delay, I was tempted to drive around the van. Behind me a handsome Spanish woman sat at the wheel of an open-topped Mercedes, remaking her lipstick over a strong mouth designed for any activity other than eating. Intrigued by her lazy sexual confidence, I smiled as she fingered her mascara and lightly brushed the undersides of her eyelashes like an indolent lover. Who was she – a nightclub cashier, a property tycoon's mistress, or a local prostitute returning to La Linea with a fresh stock of condoms and sex aids?

She noticed me watching her in my rear-view mirror and snapped down her sun vizor, waking both of us from this dream of herself. She swung the steering wheel and pulled out to pass me, baring her strong teeth as she slipped below a no-entry sign.

I started my engine and was about to follow her, but the soldier fumbling among the plastic dolls turned to bellow at me.

'Acceso prohibido…!'