Bernard Cornwell

Agincourt

Agincourt

is for my granddaughter,

Esme Cornwell,

with love.

Agincourt is one of the most instantly and vividly visualized of all epic passages in English history…. It is a victory of the weak over the strong, of the common soldier over the mounted knight, of resolution over bombast…. It is also a story of slaughter-yard behaviour and of outright atrocity.

…there is a multitude of slain, and a great number of carcasses; and there is none end of their corpses: they stumble upon their corpses.

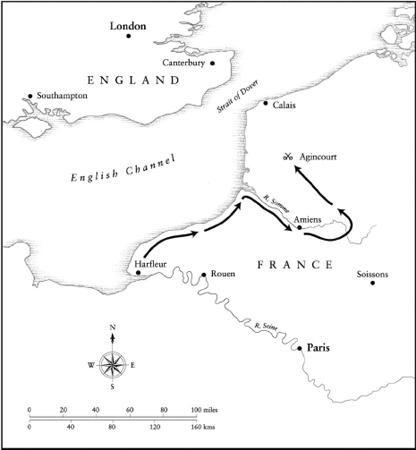

Map

Prologue

On a winter’s day in 1413, just before Christmas, Nicholas Hook decided to commit murder.

It was a cold day. There had been a hard frost overnight and the midday sun had failed to melt the white from the grass. There was no wind so the whole world was pale, frozen and still when Hook saw Tom Perrill in the sunken lane that led from the high woods to the mill pastures.

Nick Hook, nineteen years old, moved like a ghost. He was a forester and even on a day when the slightest footfall could sound like cracking ice he moved silently. Now he went upwind of the sunken lane where Perrill had one of Lord Slayton’s draft horses harnessed to the felled trunk of an elm. Perrill was dragging the tree to the mill so he could make new blades for the water wheel. He was alone and that was unusual because Tom Perrill rarely went far from home without his brother or some other companion, and Hook had never seen Tom Perrill this far from the village without his bow slung on his shoulder.

Nick Hook stopped at the edge of the trees in a place where holly bushes hid him. He was one hundred paces from Perrill, who was cursing because the ruts in the lane had frozen hard and the great elm trunk kept catching on the jagged track and the horse was balking. Perrill had beaten the animal bloody, but the whipping had not helped and Perrill was just standing now, switch in hand, swearing at the unhappy beast.

Hook took an arrow from the bag hanging at his side and checked that it was the one he wanted. It was a broadhead, deep-tanged, with a blade designed to cut through a deer’s body, an arrow made to slash open arteries so that the animal would bleed to death if Hook missed the heart, though he rarely did miss. At eighteen years old he had won the three counties’ match, beating older archers famed across half England, and at one hundred paces he never missed.

He laid the arrow across the bowstave. He was watching Perrill because he did not need to look at the arrow or the bow. His left thumb trapped the arrow, and his right hand slightly stretched the cord so that it engaged in the small horn-reinforced nock at the arrow’s feathered end. He raised the stave, his eyes still on the miller’s eldest son.

He hauled back the cord with no apparent effort though most men who were not archers could not have pulled the bowstring halfway. He drew the cord all the way to his right ear.

Perrill had turned to stare across the mill pastures where the river was a winding streak of silver under the winter-bare willows. He was wearing boots, breeches, a jerkin, and a deerskin coat and he had no idea that his death was a few heartbeats away.

Hook released. It was a smooth release, the hemp cord leaving his thumb and two fingers without so much as a tremor.

The arrow flew true. Hook tracked the gray feathers, watching as the steel-tipped tapered ash shaft sped toward Perrill’s heart. He had sharpened the wedge-shaped blade and knew it would slice through deerskin as if it were cobweb.

Nick Hook hated the Perrill family, just as the Perrills hated the Hooks. The feud went back two generations, to when Tom Perrill’s grandfather had killed Hook’s grandfather in the village tavern by stabbing him through the eye with a poker. The old Lord Slayton had declared it a fair fight and refused to punish the miller, and ever since the Hooks had tried to get revenge.

They never had. Hook’s father had been kicked to death in the yearly football match and no one had ever discovered who had killed him, though everyone knew it must have been the Perrills. The ball had been kicked into the rushes beyond the manor orchard and a dozen men had chased after it, but only eleven came out. The new Lord Slayton had laughed at the idea of calling the death murder. “If you hanged a man for killing in a game of football,” he had said, “then you’ll hang half England!”

Hook’s father had been a shepherd. He left a pregnant widow and two sons, and the widow died within two months of her husband’s death as she gave birth to a stillborn daughter. She died on the feast day of Saint Nicholas, which was Nick Hook’s thirteenth birthday, and his grandmother said the coincidence proved that Nick was cursed. She tried to lift the curse with her own magic. She stabbed him with an arrow, driving the point deep into his thigh, then told him to kill a deer with the arrow and the curse would go away. Hook had poached one of Lord Slayton’s hinds, killing it with the bloodstained arrow, but the curse had remained. The Perrills lived and the feud went on. A fine apple tree in the garden of Hook’s grandmother had died, and she insisted it had been old mother Perrill who had blighted the fruit. “The Perrills always have been putrid turd-sucking bastards,” his grandmother said. She put the evil eye on Tom Perrill and on his younger brother, Robert, but old mother Perrill must have used a counter-spell because neither fell ill. The two goats that Hook kept on the common disappeared, and the village reckoned it had to be wolves, but Hook knew it was the Perrills. He killed their cow in revenge, but it was not the same as killing them. “It’s your job to kill them,” his grandmother insisted to Nick, but he had never found the opportunity. “May the devil make you spit shit,” she cursed him, “and then take you to hell.” She threw him from her home when he was sixteen. “Go and starve, you bastard,” she snarled. She was going mad by then and there was no arguing with her, so Nick Hook left home and might well have starved except that was the year he came first in the six villages’ competition, putting arrow after arrow into the distant mark.

Lord Slayton made Nick a forester, which meant he had to keep his lordship’s table heavy with venison. “Better you kill them legally,” Lord Slayton had remarked, “than be hanged for poaching.”

Now, on Saint Winebald’s Day, just before Christmas, Nick Hook watched his arrow fly toward Tom Perrill.

It would kill, he knew it.

The arrow flew true, dipping slightly between the high, frost-bright hedges. Tom Perrill had no idea it was coming. Nick Hook smiled.

Then the arrow fluttered.

A fledging had come loose, its glue and binding must have given way and the arrow veered leftward to slice down the horse’s flank and lodge in its shoulder. The horse whinnied, reared and lunged forward, jerking the great elm trunk loose from the frozen ruts.

Tom Perrill turned and stared up at the high wood, then understood a second arrow could follow the first and so turned again and ran after the horse.

Nick Hook had failed again. He was cursed.

Lord Slayton slumped in his chair. He was in his forties, a bitter man who had been crippled at Shrewsbury by a sword thrust in the spine and so would never fight another battle. He stared sourly at Nick Hook. “Where were you on Saint Winebald’s Day?”