Aztec Autumn (Aztec #2)

by Gary Jennings

I

I can still see him burning.

On that long-ago day when I watched the man being set afire, I was already eighteen years old, so I had seen other people die, whether given in sacrifice to the gods or executed for some outrageous crime or simply dead by accident. But the sacrifices had always been done by means of the obsidian knife that tears out the heart. The executions had always been done with the maquahuitl sword or with arrows or with the strangling "flower garland." The accidental deaths had mostly been the drownings of fishermen from our seaside city who somehow fell afoul of the water goddess. In the years since that day, too, I have seen people die in war and in various other ways, but never before then had I seen a man deliberately put to death by fire, nor have I since.

I and my mother and my uncle were among the vast crowd commanded by the city's Spanish soldiers to attend the ceremony, so I supposed that this event was intended to be some sort of object lesson to all of us non-Spaniards. Indeed, the soldiers collected and prodded and herded so many of us into the city's central square that we were crammed shoulder to shoulder. Within a space kept clear by a cordon of other soldiers, a metal post stood fixed into the flagstones of the square. To one side of it had been built a platform for the occasion, and on it sat or stood a number of Spanish Christian priests, all clad in flowing black gowns, as are our own priests.

Two burly Spanish guards brought the condemned man and roughly shoved him into that cleared space. When we saw that he was not a Spaniard, pale and bearded, but one of our own people, I heard my mother sigh, "Ayya ouiya..." and so did many others in the crowd. The man wore a loose, shapeless and colorless garment and, on his head, a scraggly crown made of straw. His only adornment that I could see was a pendant of some kind—it flashed when it caught the sun—hanging from a thong about his neck.

The man was quite old, even older than my uncle, and he put up no struggle against his guards. The man seemed, in fact, either resigned to his fate or indifferent to it, so I do not know why he was immediately encumbered by a heavy restraint. A tremendous piece of metal chain was hung upon him, a chain of such dimensions that a single link of it was big enough to be forced over his head to pinion his neck. That chain was then fixed to the upright post, and the guards began piling about his feet a heap of kindling wood. While that was being done, the oldest of the priests on the platform—the chief of them, I assumed—spoke to the prisoner, addressing him by a Spanish name, "Juan Damasceno." Then he commenced a long harangue, naturally in Spanish, which at that time I had not yet learned. But a younger priest, dressed in slightly different vestments, translated his chief's words—to my considerable surprise—into fluent Nahuatl.

This enabled me to comprehend that the old priest was reciting the charges against the condemned man, and also that he was—in a voice alternately unctuous and angry—trying to persuade the man to make amends or show contrition or something of the sort. But even when translated into my native language, the terms and expressions employed by the priest were a bafflement to me. After a long and wordy while of this, the prisoner was given leave to speak. He did so in Spanish, and when that was translated into Nahuatl, I understood him very clearly.

"Your Excellency, once when I was still a small child I vowed to myself that if ever I were selected for the Flowery Death, even on an alien altar, I would not degrade the dignity of my going."

Juan Damasceno spoke nothing more than that, but among the priests and guards and other officials there ensued a great deal of discourse and conferring and gesticulation—before finally a stern command was uttered, and one of the soldiers set a torch to the pile of wood at the prisoner's feet.

As is well known, the gods and goddesses take mischievous delight in perplexing us mortals. They frequently confound our best intentions and complicate our most straightforward plans and thwart even the least of our ambitions. Often they can do such things with ease, simply by arranging what appears to be a matter of coincidence. And if I did not know better, I would have said that it was mere coincidence that brought us three—my uncle, Mixtzin, his sister Cuicani and her son, myself, Tenamaxtli—to the City of Mexico on that particular day.

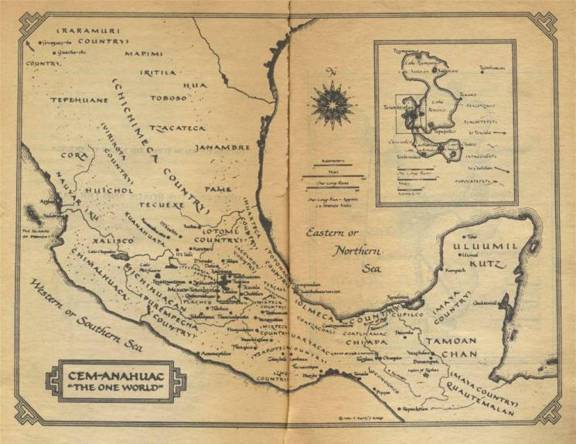

Fully twelve years previous, in our own city of Aztlan, the Place of Snowy Egrets, far to the northwest, on the coast of the Western Sea, we had heard the first startling news: that The One World had been invaded by pale-skinned and heavily bearded strangers. It was said that they had come from across the Eastern Sea in huge houses that floated on the water and were propelled by immense birdlike wings. I was only six years old at that time, with a whole seven years to wait before I could don, beneath my mantle, the maxtlatl loincloth that signifies the attainment of manhood. Hence I was an insignificant person, of no consequence at all. Nevertheless, I was precociously inquisitive and very sharp of ear. Also, my mother Cuicani and I did reside in the Aztlan palace with my Uncle Mixtzin and his son Yeyac and daughter Ameyatl, so I was always able to hear whatever news arrived and whatever comment it provoked among my uncle's Speaking Council.

As is indicated by the -tzin suffixion to my uncle's name, he was a noble, the highest noble among us Azteca, being the Uey-Tecutli—the Revered Governor—of Aztlan. Some while earlier, when I was just a toddling babe, the late Uey-Tlatoani Motecuzoma, Revered Speaker of the Mexica. the most powerful nation in all The One World, had accorded our then-small village the status of "autonomous colony of the Mexica." He ennobled my Uncle Mixtli as the Lord Mixtzin, and set him to govern Aztlan, and bade him build the place into a prosperous and populous and civilized colony of which the Mexica could be proud. So, although we were exceedingly far distant from the capital city of Tenochtitlan—The Heart of The One World—Motecuzoma's swift-messengers routinely brought to our Aztlan palace, as to other colonies, any news deemed of interest to his under-governors. Of course, the news of those intruders from beyond the sea was anything but routine. It caused no small consternation and speculation among Aztlan's Speaking Council.

"In the ancient archives of various nations of our One World," said old Canautli, our Rememberer of History, who also happened to be the grandfather of my uncle and my mother, "it is recorded that the Feathered Serpent, the once-greatest of all monarchs, Quetzalcoatl of the Tolteca—he who eventually was worshiped as the greatest of gods—was described as having a very white skin and a bearded face."

"Are you suggesting—?" began another member of the Council, a priest of our war god Huitzilopochtli. But Canautli overrode him, as I could have told the priest he would, because I well knew how my great-grandfather loved to talk.

"It is also recorded that Quetzalcoatl abdicated his rule of the Tolteca as a consequence of his having done something shameful. His people might never have known of it, but he confessed to it. In a fit of intoxication—after overindulgence in the drunk-making octli beverage—he committed the act of ahuilnema with his own sister. Or, some say, with his own daughter. The Tolteca so much adored the Feathered Serpent that they doubtless would have forgiven him that misconduct, but he could not forgive himself."

Several of the councillors nodded solemnly. Canautli went on: