This book made available by the Internet Archive.

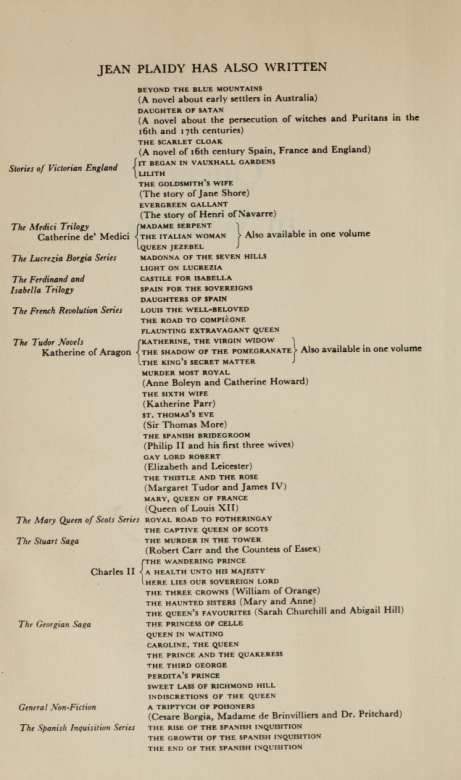

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lives of the Queens of England of the House of Hanover

The Four Georges

Caroline of Anshach

Caroline the Illustrations

Caroline of England

The House of Hanover

A History of the Four Georges and William IV

The Four Georges

British History in the Nineteenth Century

Sir Robert Walpole

George II and His Ministers

Lord Herveys Memoirs

The Dictionary of National Biography

British History History of England

England Under the Hanoverians

The First George

Eighteenth Century London Life

Bishop Burnett's History of His Own Time

A Constitutional King, George the First

Letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montague

Notes on British History

Dr. Doran Sir Charles Petrie R. L. Arkell W. H. Wilkins Peter Quennell Alvin Redman

Justin McCarthy W. M. Thackeray

G. M. Trevelyan

J. H. Plumb

Reginald Lucas

Edited by Romney wick

Edited by Sir Stephen and Sir Lee

John Wade

William Hickman Smith Aubrey

Sir Charles Grant Robertson

Lewis Melville

Rosamund Baynes Powell

Sir H. M. Impert-Terry

William Edwards

Sedg-

Leslie Sidney

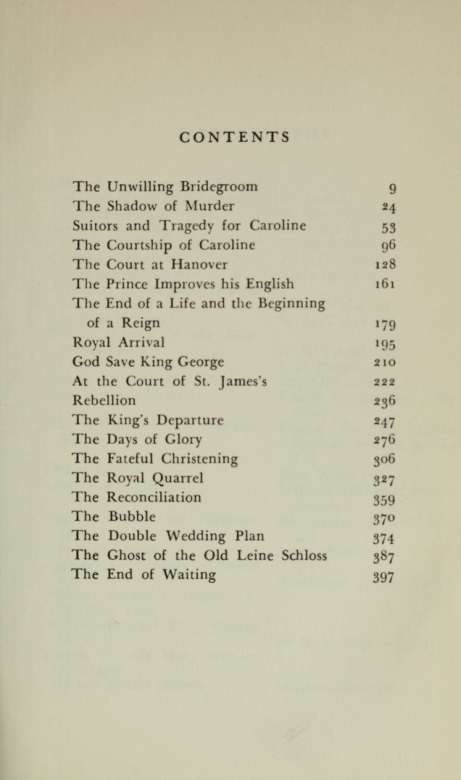

The Unwilling Bridegroom

Sophia Charlotte, Electrcss of Brandenburg, was discussing the possibility of a marriage for her dear but sadly impoverished friend Eleanor Erdmuthe Louisa, widowed Margravine of Ansbach.

*'For you see, my dear Frederick, her position is intolerable as it stands and what will become of that poor child of hers if her mother has no position in the world?"

Frederick, Elector of Brandenburg, smiled at his wife. He rarely smiled when he was not with her for his was far from a genial nature; but since their marriage he had never ceased to be delighted with her and had been a faithful husband which was something of a miracle when the way of life among German princelings was promiscuous by habit and the coarser the more natural.

But no other German prince possessed a wife like Sophia Charlotte. She was the most beautiful Princess in Germany, so he believed: as soon as he had seen her he had been struck by this unusual beauty, so outstanding among the buxom ladies of his previous acquaintance. She had a grace and charm in-

herited from her Stuart ancestors for her mother was Sophia, Electress of Hanover and her mother had been Elizabeth of Bohemia daughter of James I of England. The Stuart charm was very noticeable in Sophia Charlotte—tempered, thought Frederick, with good sound German common sense. Charm and good sense! What a combination I

**Well, we must bring about this marriage. It would be excellent from all points of view," he said.

*'It would give me great pleasure to see her happy. Poor soul, I fear she has no easy time in Ansbach with that stepson of hers. I believe he always resented his father's second marriage and now he has a chance to express his disapproval. It's no atmosphere in which to bring up children."

"Nothing could suit us better than to see a friend of ours married into Saxony. John George has been a cause of trouble since he inherited. And I believe that woman of his is in the pay of Austria."

"Then he needs marriage with a woman like Eleanor to break the association. Though I've heard that his passion for Magdalen von Roohlitz is quite violent and she has great power over him."

"Eleanor will break that."

Sophia Charlotte was dubious. Eleanor was a dear creature but meek and although pretty enough in her way, perhaps not persuasively charming or erotically skilled enough to break the hold of a sensuous woman like von Roohlitz.

Sophia Charlotte's inclination was to turn away from unpleasantness and such relationships as that between the dissolute Elector of Saxony and his mistress was in her opinion decidedly unpleasant; but she was never one to shirk the distasteful at the expense of duty; and she was deeply concerned about her friend.

Her husband looked at her a little wistfully. He would have been delighted if she had taken more interest in politics. He had often visualized an ideal relationship. She was the only woman in the world with whom he would have shared his powers—and she did not want a share in it. If she had brought that penetrating mind of hers to the study of politics, if they had worked together, what a pair they would have made! But

no! She preferred literature, music, art and discussion to statescraft. She would converse learnedly with theologians on the possibility of an after-life but had little concern for the affairs of her husband's electorate.

Yet what could he do but indulge her for his greatest desire was to please her. There she sat now—serene, almost unbelievably beautiful, gravely discussing this marriage—not because the alliance would help to break friendship between Saxony and Austria and turn it towards Brandenburg where it was needed, but because her friend and prot^g^e, poor widowed Eleanor, needed a home and settled life for her children.

Her children! That was at the root of the matter. He and Sophia Charlotte had one son, Frederick William—and the little boy was already showing signs of an ungovernable temper—and she longed for a daughter, preferably like Eleanor's who was a pretty little girl, now about eight years old, flaxen-haired, and plump with bright blue enquiring eyes. He had seen Sophia Charlotte's eyes on little Wilhelmina Caroline. And it was to provide security for the child that Sophia Charlotte wanted this match.

He went on: "When she is married into Saxony it will be easier for her to provide for her children's future."

"Poor little Caroline!" She was referring to Wilhelmina Caroline who was known by her second name. "That stepbrother who is now the Margrave resents them at Ansbach. Eleanor was delighted when I suggested she should come to us in Berlin."

"I'm not surprised, my dear. You make them very welcome and it is, as we all know, an honour to be a guest at Liitzen-burg which you have made comparable, so they tell me, with the Palace of Versailles."

"That is an exaggeration. Nothing on earth could compare with Versailles. We are none of us in a position to set ourselves up as little Kings of France. Nor do we wish to. Liitzenburg is ours ... we have made it as it is and certainly we have not tried to imitate Louis."

"You have made it so, my dear, not I," he reminded her.

"But for your generosity I should never have had the opportunity." She smiled at him wishing she could feel more strongly

towards him. But she felt no love for him nor for any man. Moreover he was middleaged and deformed, and when she had first seen him she had been horrified, but her mother had warned her years before that all Princesses must accept the marriages which were made for them and even if they must go to bed with a gorilla for the sake of the state they should not complain. Frederick was no gorilla—merely in her young eyes an unattractive, unshapely old man whom she had learned to tolerate; and his indulgence to her had touched her, for not only did he wish to please her by giving her gifts like the beautiful castle of Liitzenburg, not only did he allow her to invite her own circle of friends there, even though they were of no interest to him, but he w^as actually in awe of her. When she considered the promiscuity of her father, the Elector of Hanover, and the crudeness of her eldest brother George Lewis with his dreadful mistresses; when she considered her dignified mother's resignation and the manner in which George Lewis treated his beautiful wife, Sophia Dorothea, she must think she was very fortunate.