Arbuthnot considered for a moment or two.

“No,” he said. “Nothing at all. Unless–” he hesitated.

“But yes, continue, I pray of you.”

“Well, it’s nothing really,” said the Colonel slowly. “But you said anything.”

“Yes, yes. Go on.”

“Oh! it’s nothing. A mere detail. But as I got back to my compartment I noticed that the door of the one beyond mine – the end one, you know–”

“Yes, No. 16.”

“Well, the door of it was not quite closed. And the fellow inside peered out in a furtive sort of way. Then he pulled the door to quickly. Of course I know there’s nothing in that – but it just struck me as a bit odd. I mean, it’s quite usual to open a door and stick your head out if you want to see anything. But it was the furtive way he did it that caught my attention.”

“Ye-es,” said Poirot doubtfully.

“I told you there was nothing to it,” said Arbuthnot, apologetically. “But you know what it is – early hours of the morning – everything very still. The thing had a sinister look – like a detective story. All nonsense really.”

He rose. “Well, if you don’t want me any more–”

“Thank you, Colonel Arbuthnot, there is nothing else.”

The soldier hesitated for a minute. His first natural distaste for being questioned by “foreigners” had evaporated.

“About Miss Debenham,” he said rather awkwardly. “You can take it from me that she’s all right. She’s a pukka sahib.”

Flushing a little, he withdrew.

“What,” asked Dr. Constantine with interest, “does a pukka sahib mean?”

“It means,” said Poirot, “that Miss Debenham’s father and brothers were at the same kind of school as Colonel Arbuthnot was.”

“Oh! said Dr. Constantine, disappointed. “Then it has nothing to do with the crime at all.”

“Exactly,”, said, Poirot.

He fell into a reverie, beating a light tattoo on the table. Then he looked up.

“Colonel Arbuthnot smokes a pipe,” he said. “In the compartment of Mr. Ratchett I found a pipe-cleaner. Mr. Ratchett smoked only cigars.”

“You think–?”

“He is the only man so far who admits to smoking a pipe. And he knew of Colonel Armstrong – perhaps actually did know him, though he won’t admit it.”

“So you think it possible–?”

Poirot shook his head violently.

“That is just it – it is impossible – quite impossible – that an honourable, slightly stupid, upright Englishman should stab an enemy twelve times with a knife! Do you not feel, my friends, how impossible it is?”

“That is the psychology,” said M. Bouc.

“And one must respect the psychology. This crime has a signature, and it is certainly not the signature of Colonel Arbuthnot. But now to our next interview.”

This time M. Bouc did not mention the Italian. But he thought of him.

9. The Evidence of Mr. Hardman

The last of the first-class passengers to be interviewed, Mr. Hardman, was the big flamboyant American who had shared a table with the Italian and the valet.

He wore a somewhat loud check suit, a pink shirt, and a flashy tie-pin, and was rolling something round his tongue as he entered the dining-car. He had a big, fleshy, coarse-featured face, with a good-humoured expression.

“Morning, gentlemen,” he said. “What can I do for you?”

“You have heard of this murder, Mr. – er – Hardman?”

“Sure.” He shifted the chewing gum deftly.

“We are of necessity interviewing all the passengers on the train.”

“That’s all right by me. Guess that’s the only way to tackle the job.”

Poirot consulted the passport lying in front of him.

“You are Cyrus Bethman Hardman, United States subject, forty-one years of age, travelling salesman for typewriting ribbons?”

“O.K. That’s me.”

“You are travelling from Stamboul to Paris?”

“That’s so.”

“Reason?”

“Business.”

“Do you always travel first-class, Mr. Hardman?”

“Yes, sir. The firm pays my travelling expenses. “ He winked.

“Now, Mr. Hardman, we come to the events of last night.”

The American nodded.

“What can you tell us about the matter?”

“Exactly nothing at all.”

“Ah, that is a pity. Perhaps, Mr. Hardman, you will tell us exactly what you did last night from dinner onwards?”

For the first time the American did not seem ready with his reply. At last he said: “Excuse me, gentlemen, but just who are you? Put me wise.”

“This is M. Bouc, a director of the Compagnie des Wagons Lits. This gentleman is the doctor who examined the body.”

“And you yourself?”

“I am Hercule Poirot. I am engaged by the company to investigate this matter.”

“I’ve heard of you,” said Mr. Hardman. He reflected a minute or two longer. “Guess I’d better come clean.”

“It will certainly be advisable for you to tell us all you know,” said Poirot drily.

“You’d have said a mouthful if there was anything I did know. But I don’t. I know nothing at all – just as I said. But I ought to know something. That’s what makes me sore. I ought to.”

“Please explain, Mr. Hardman.”

Mr. Hardman sighed, removed the chewing gum, and dived into a pocket. At the same time his whole personality seemed to undergo a change. He became less of a stage character and more of a real person. The resonant nasal tones of his voice became modified.

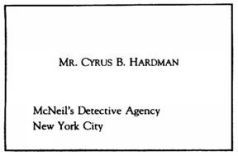

“That passport’s a bit of bluff,” he said. “That’s who I really am.”

Poirot scrutinised the card flipped across to him. M. Bouc peered over his shoulder.

Poirot knew the name as that of one of the best-known and most reputable private detective agencies in New York.

“Now, Mr. Hardman,” he said, “let us hear the meaning of this.”

“Sure. Things came about this way. I’d come over to Europe trailing a couple of crooks – nothing to do with this business. The chase ended in Stamboul. I wired the Chief and got his instructions to return, and I would have been making my tracks back to little old New York when I got this.”

He pushed across a letter.

THE TOKATLIAN HOTEL

Dear Sir:

You have been pointed out to me as an operative of the McNeil Detective Agency. Kindly report at my suite at four o’clock this afternoon.

S. E. RATCHETT

“Eh bien?”

“I reported at the time stated, and Mr. Ratchett put me wise to the situation. He showed me a couple of letters he’d got.”

“He was alarmed?”

“Pretended not to be, but he was rattled, all right. He put up a proposition to me. I was to travel by the same train as he did to Parrus and see that nobody got him. Well, gentlemen, I did travel by the same train, and in spite of me, somebody did get him. I certainly feel sore about it. It doesn’t look any too good for me.”

“Did he give you any indication of the line you were to take?”

“Sure. He had it all taped out. It was his idea that I should travel in the compartment alongside his. Well, that blew up right at the start. The only place I could get was berth No. 16, and I had a job getting that. I guess the conductor likes to keep that compartment up his sleeve. But that’s neither here nor there. When I looked all round the situation, it seemed to me that No. 16 was a pretty good strategic position. There was only the dining-car in front of the Stamboul sleeping-car, and the door onto the platform at the front end was barred at night. The only way a thug could come was through the rear-end door to the platform, or along the train from the rear, and in either case he’d have to pass right by my compartment.”

“You had no idea, I suppose, of the identity of the possible assailant?”

“Well, I knew what he looked like. Mr. Ratchett described him to me.”