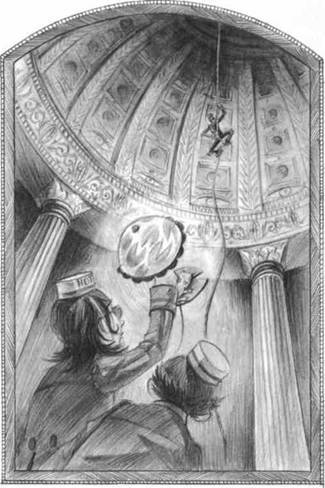

"Good evening, Baudelaires," the man said. "Forgive me for not revealing myself earlier, but I had to be sure that you were who I thought you were. It must have been very confusing to wander around this hotel without a catalog to help you."

"So there is a catalog?" Klaus asked.

"Of course there's a catalog," the man said. "You don't think I'd organize this entire building according to the Dewey Decimal System and then neglect to add a catalog, do you?"

"But where is the catalog?" Violet asked.

The man smiled. "Come outside," he said, "and I'll show you."

"Trap," Sunny murmured to her siblings, who nodded in agreement. "We're not following you," Violet said, "until we know that you're someone we can trust."

The man smiled. "I don't blame you for being suspicious," he said. "When I used to meet your father, Baudelaires, we would recite the work of an American humorist poet of the nineteenth century, so we could recognize one another in our disguises." He stopped in the middle of the lobby, and with a gesture from one of his odd, skinny arms, he began to recite a poem:

"So oft in theologic wars, The disputants, I ween, Rail on in utter ignorance Of what each other mean, And prate about an Elephant Not one of them has seen!"

The words of the American humorist poets of the nineteenth century are often confusing, as they are liable to use such terms as "oft," which is a nineteenth-century abbreviation for "often"; "disputants," which refers to people who are arguing; "ween," which means "think"; and "rail on," which means to bicker for hours on end, the way you might do with a family member who is particularly bossy. Such poets might use the word "prate," which means "chatter," and they might spend an entire stanza discussing "theologic wars," a term which refers to arguing over what different people believe, the way you might also do with a family member who is particularly bossy. Even the Baudelaires, who'd had the works of American humorist poets of the nineteenth century recited to them many times over their childhood, had trouble understanding everything in the stanza, which simply made the point that all of the blind men in the poem were arguing pointlessly. But Violet, Klaus, and Sunny did not need to know exactly what the stanza meant. They only needed to know who wrote it.

"John Godfrey Saxe," said Sunny with a smile.

"Very good," the man said, and he walked across the shiny, silent floor of the lobby, pulling the rope down from the ceiling and tucking it into his belt.

"And who are you?" Violet called.

"Can't you guess?" the man asked, pausing at the large, curved entrance. The Baudelaires hurried to catch up with him as he turned to exit the hotel.

"Frank?" Klaus said.

"No," the man said, and began to walk down the stairs. The Baudelaires took a step outside, where the croaking of the frogs in the pond was considerably louder, although the children could not see the pond through the cloud of steam coming from the funnel. Violet, Klaus, and Sunny looked at one another cautiously, and then began to follow.

"Ernest?" Sunny asked.

The man smiled, and kept walking down the stairs, disappearing into the steam. "No," he said, and the Baudelaire orphans stepped out of the hotel and disappeared along with him.

CHAPTEREight

The word "denouement" is not only the name of a hotel or the family who manages it, particularly nowadays, when the hotel and all its secrets have almost been forgotten, and the surviving members of the family have changed their names and are working in smaller, less glamorous inns. "Denouement" comes from the French, who use the word to describe the act of untying a knot, and it refers to the unraveling of a confusing or mysterious story, such as the lives of the Baudelaire orphans, or anyone else you know whose life is filled with unanswered questions. The denouement is the moment when all of the knots of a story are untied, and all the threads are unraveled, and everything is laid out clearly for the world to see. But the denouement should not be confused with the end of a story. The denouement of "Snow White," for instance, occurs at the moment when Ms. White wakes up from her enchanted sleep, and decides to leave the dwarves behind and marry the handsome prince, and the mysterious old woman who gave her an apple has been exposed as the treacherous queen, but the end of "Snow White" occurs many years later, when a horseback riding accident plunges Ms. White into a fever from which she never recovers. The denouement of "Goldilocks and the Three Bears" occurs at the moment when the bears return home to find Goldilocks napping on their private property, and either chase her away from the premises, or eat her, depending on which version you have in your library, but the end of "Goldilocks and the Three Bears" occurs when a troop of young scouts neglect to extinguish their campfire and even the efforts of a volunteer fire department cannot save most of the wildlife from certain death. There are some stories in which the denouement and the end occur simultaneously, such as La Forzadel Destino, in which the characters recognize and destroy one another over the course of a single song, but usually the denouement of a story is not the last event in the heroes' lives, or the last trouble that befalls them. It is often the second-to-last event, or the penultimate peril. As the Baudelaire orphans followed the mysterious man out of the hotel and through the cloud of steam to the edge of the reflective pond, the denouement of their story was fast approaching, but the end of their story still waited for them, like a secret still covered in fog, or a distant island in the midst of a troubled sea, whose waves raged against the shores of a city and the walls of a perplexing hotel.

"You must have thousands of questions, Baudelaires," said the man. "And just think- right here is where they can be answered."

"Who are you?" Violet asked.

"I'm Dewey Denouement," Dewey Denouement replied. "The third triplet. Haven't you heard of me?"

"No," Klaus said. "We thought there were only Frank and Ernest."

"Frank and Ernest get all the attention," Dewey said. "They get to walk around the hotel managing everything, while I just hide in the shadows and wind the clock." He gave the Baudelaires an enormous sigh, and scowled into the depths of the pond. "That's what I don't like about V.F.D.," he said. "All the smoke and mirrors."

"Smoke?" Sunny asked.

"'Smoke and mirrors,'" Klaus explained, "means 'trickery used to cover up the truth.' But what does that have to do with V.F.D.?"

"Before the schism," Dewey said, "V.F.D. was like a public library. Anyone could join us and have access to all of the information we'd acquired. Volunteers all over the globe were reading each other's research, learning of each other's observations, and borrowing each other's books. For a while it seemed as if we might keep the whole world safe, secure, and smart."

"It must have been a wonderful time," Klaus said.

"I scarcely remember it," Dewey said. "I was four years old when the schism began. I was scarcely tall enough to reach my favorite shelf in the family library-the books labeled 020. But one night, just as our parents were hanging balloons for our fifth birthday party, my brothers and I were taken."

"Taken where?" Violet asked.

"Taken by whom?" Sunny asked.

"I admire your curiosity," Dewey said. "The woman who took me said that one can remain alive long past the usual date of disintegration if one is unafraid of change, insatiable in intellectual curiosity, interested in big things, and happy in small ways. And she took me to a place high in the mountains, where she said such things would be encouraged."