"You… I… go Helmuth," suggested Luna suddenly, waving a delicate hand.

I agreed, wondering what a Helmuth was; it was a new word to me, and, as far as I was concerned, could have been anything from a new type of jet-engine to a particularly low night-club. However, I was willing to try anything once, especially if it turned out to be a nightclub. We walked down the musically squeaking, creaking, groaning and rustling avenue of bamboo, and then came to a large area of lawn, dotted with gigantic palm-trees, their trunks covered with parasitic plants and orchids. We walked through these towards a long, low red brick building, while the humming-birds* flipped and whirred around us, gleaming and changing with the delicate sheen one sees on a soap bubble. Luna led me through gauze-covered doors into a large cool dining-room, and there, sitting in solitary state at the end of a huge table, devouring breakfast, was a man of about thirty with barley-sugar coloured hair, vivid blue eyes, and a leathery, red, humorous face. He looked up as we entered and gave us a wide, impish grin.

"Helmuth," said Luna, pointing to this individual, as if he had performed a particularly difficult conjuring trick. Helmuth rose from the table and extended a large, freckled hand.

"Hello," he said, crashing my hand in his, "I'm Helmuth. Sit down and have some breakfast, eh?"

I explained that I had already had some breakfast, and so Helmuth returned to his victuals, talking to me between mouthfuls, while Luna, seated the other side of the table, drooped languidly in a chair and hummed softly to himself.

"Charles tells me you want animals, eh?" said Helmuth. "Well, we don't know much about animals here. There are animals, of course, up in the hills, but I don't know what you'll get in the villages. Not much, I should think. However, when I've finished eating we go see,eh?"

When Helmuth had assured himself, somewhat reluctantly, that there was nothing edible left on the table, he hustled Luna and myself out to his station-wagon,* piled us in and drove down to the village, over the dusty, rutted roads that would, at the first touch of rain, turn into glutinous mud.

The village was a fairly typical one, consisting of small shacks with walls built out of the jagged off-cuts from the saw mill, and whitewashed. Each stood in its own little patch of ground, surrounded by a bamboo fence, and these gardens were sometimes filled with a strange variety of old tins, kettles and broken barrels each brimming over with flowers. Wide ditches full of muddy water separated these "gardens" from the road, and were spanned at each front gate by a small, rickety bridge of roughly-nailed branches. It was at one of these little shanties that Helmuth stopped. He peered hopefully into the riot of pomegranate trees, covered with red flowers, that filled the tiny garden*

"Here, the other day, I think I see a parrot," he explained.

We left the station-wagon and crossed the rickety little bridge that led to the bamboo gate. Here we clapped our hands and waited patiently. Presently, from inside the little shack, erupted a brood of chocolate-coloured children, all dressed in clean but tattered clothing, who lined up like a defending army and regarded us out of black eyes, each, without exception, sucking its thumb vigorously. They were followed by their mother, a short, rather handsome Indian woman with a shy smile.

"Enter, senores, enter," she called, beckoning us into the garden.

We went in, and, while Luna crouched down and conducted a muttered conversation with the row of fascinated children, Helmuth, exuding good-will and personality,* beamed at the woman.

"This senor," he said, gripping my shoulder tightly, as if fearful that I might run away, "this senor wants bichos, live bichos, eh? Now, the other day when I passed your house, I saw that you possessed a parrot, a very common and rather ugly parrot of a kind that I have no doubt the senor will despise. Nevertheless, I am' bound to show it to him, worthless though it is."

The woman bristled.

"It is a beautiful parrot," she said shrilly and indignantly, "a very beautiful parrot, and one, moreover, of a kind that is extremely rare. It comes from high up in the mountains."

"Nonsense," said Helmuth firmly, "I have seen many like it in the market in Jujuy, and they were so common they were practically having to give them away. This one is undoubtedly one of those."

"The senor is mistaken," said the woman, "this is a most unusual bird of great beauty and tameness."

"I do not think it is beautiful," said Helmuth, and added loftily, "and as for its tameness, it is a matter of indifference to the senor whether it be tame or as wild as a puma."

I felt it was about time I entered the fray.

"Er… Helmuth," I said tentatively.

"Yes?" he said, turning to me and regarding me with his blue eyes flashing with the light of battle.

"I don't want to interfere, but wouldn't it be a good idea if I saw the bird first, before we start bargaining? I mean, it might be something very common, or something quite rare."

"Yes," said Helmuth, struck by the novelty of this idea, "yes, let us see the bird."

He turned and glared at the woman.

"Where is this wretched bird of yours?" he inquired.

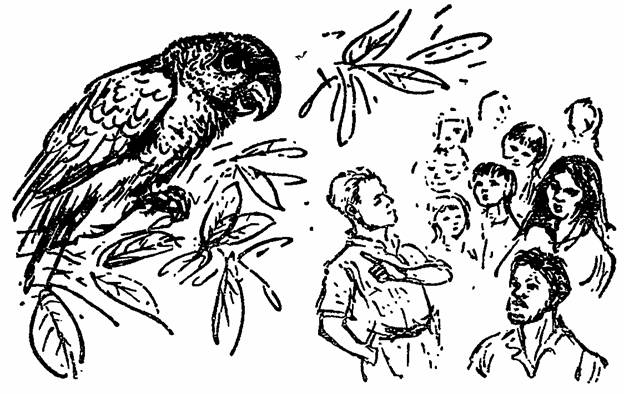

The woman pointed silently over my left shoulder, and turning round I found that the parrot had been perching among the green leaves of the pomegranate tree some three feet away, an interested spectator of our bargaining. As soon as I saw it I knew that I must have it, for it was a rarity, a red-fronted Tucuman Amazon,* a bird which was, to say the least of it, unusual in European collections. He was small for an Amazon parrot, and his plumage was a rich grass-green with more than a tinge of yellow in it here and there; he had bare white rings round his dark eyes, and the whole of his forehead was a rich scarlet. Where the feathering ended on each foot he appeared to be wearing orange garters. I gazed at him longingly. Then, trying to wipe the acquisitive* look off my face I turned to Helmuth and shrugged with elaborate unconcern, which I am sure did not deceive the parrot's owner for a moment.

"It's a rarity," I said, trying to infuse dislike and loathing for the parrot into my voice, "I must have it."

"You see?" said Helmuth, returning to the attack, "the senor says it is a very common bird, and he already has six of them down, in Buenos Aires."

The woman regarded us both with deep suspicion. I tried to look like a man who possessed six Tucuman Amazons, and who really did not care to acquire any more. The woman wavered, and then played her trump card.*

"But this one talks" she said triumphantly.

"The senor does not care if they talk or not," Helmuth countered quickly. We had by now all moved towards the bird, and were gathered in a circle round the branch on which it sat, while it gazed down at us expressionlessly.

"Blanco…, Blanco," cooed the woman, "como te va, Blanco?"*

"We will give you thirty pesos for it," said Helmuth.

"Two hundred," said the woman, "for a parrot that talks two hundred is cheap."

"Nonsense," said Helmuth, "anyway, how do we know it talks? It hasn't said anything."

"Blanco, Blanco," cooed the woman in a frenzy, "speak to Mama… speak Blanco."

Blanco eyed us all in a considering way.

"Fifty pesos, and that's a lot of money for a bird that won't talk," said Helmuth.

"Madre de Dios,* but he talks all day," said the woman, almost in tears, "wonderful things he says… he is the best parrot I have ever heard."

"Fifty pesos, take it or leave it," said Helmuth flatly.

"Blanco, Blanco, speak," wailed the woman, "say something for the senores… please."