Julia took the boy’s face in her hand. “No, they don’t! Brave Uncle Gaius escaped from the pirates.”

“He escaped?”

“Yes, indeed. And then do you know what he did? He hunted them down, and he killed them.”

“All the pirates?”

“Yes, every one! Uncle Gaius nailed them to crosses, and gave them the terrible deaths they deserved. Those awful pirates will never bother anyone ever again.”

“Because Uncle Gaius killed them!”

“That’s right. So you must have no more bad dreams about them. Now, there’s someone here to whom you must say hello.”

Julia looked up, but Lucius had disappeared.

Out in the street, Lucius coughed violently. His breath formed streams of mist in the cold air. He walked quickly, aimlessly, his thoughts a muddle; his slave had to hurry to keep up with him. His eyes welled with tears. The tears felt hot running down his cheeks. They blurred his vision. He did not see the patch of ice on the paving stones ahead of him. The slave saw, and shouted a warning, but too late.

Lucius stepped on the ice. Limbs flailing, he fell backward. He struck his head on a stone. He shuddered and twitched, then lay very still. Blood ran from his skull.

Seeing the empty look in his master’s wide-open eyes and the peculiar way his neck was twisted, the slave let out a scream, but there was nothing to be done. Lucius was dead.

CAESAR’S HEIR

44 B.C.

It was the Ides of Februarius. Since the time of King Romulus, this was the day set aside for the ritual called the Lupercalia.

The origin of the Lupercalia-the boisterous occasion when young Romulus and Remus and their friend Potitius ran about the hills of Roma naked with their faces disguised by wolfskins-was long forgotten, as were the origins of many Roman holidays. But above all else, the Romans honored the traditions that had been handed down by their ancestors. Paying scrupulous attention to the most minute details, they continued to observe many arcane rituals, sacrifices, feasts, holidays, and propitiations to the gods, long after the origins of these rites were lost.

The Roman calendar was filled with such enigmatic observances, and numerous priesthoods had been established to maintain them. Because religion determined, or at least justified, the actions of the state, senatorial committees studied lists of precedents to determine the days when certain legislative procedures could and could not be performed.

Why did the Romans adhere so faithfully to tradition? There was sound reasoning behind such devotion. The ancestors had performed certain rituals, and in return had been favored by the gods above all other people. It only made sense that living Romans, the inheritors of their predecessors’ greatness, should continue to perform those rituals precisely as handed down to them, whether they understood them or not. To do otherwise was to tempt the Fates. This logic was the bedrock of Roman conservatism.

And so, as their ancestors had done for many hundreds of years, on the day of the Lupercalia the magistrates of the city, along with the youths of noble families, stripped naked and ran through the streets of the city. They carried thongs of goat hide and cracked them in the air like whips. Young women who were pregnant or desired to become so would purposely run toward them and offer their hands to be slapped by the thongs, believing that this act would magically enhance their fertility and grant them an easy birth. Where this belief came from, no one knew, but it was part of the great compendium of beliefs that had come down to them and thus was worthy of observance.

Presiding over the festivities, seated on the Rostra upon a golden throne, arrayed in magnificent purple robes, and attended by a devoted retinue of scribes, bodyguards, military officers, and assorted sycophants, sat Gaius Julius Caesar.

At the age of fifty-six, Caesar was a handsome man. He had a trim figure, but-ironically, given his cognoman-he had lost much of his hair, especially at the crown and the temples; the remainder he combed over his forehead in a vain attempt to hide his baldness. The men around him hung on his every word. The citizens, gathered to watch the Lupercalia, gazed up at him with fear, awe, respect, hatred, and even love, but never with indifference. To all appearances, Caesar might have been a king presiding over his subjects, except for the fact that he did not wear a crown.

A lifetime of political maneuvering and military conquests had brought Caesar to this point. Early in his career, he proved to be a master of political procedure; no man could manipulate the Senate’s convoluted rules as deftly as Caesar, and many were the occasions he thwarted his rivals by invoking some obscure point of order. He had proven to be a military genius as well; in less than ten years he had conquered all of Gaul, enslaving millions and accumulating a huge fortune for himself. When his envious, fearful enemies in the Senate attempted to deprive him of his legions and his power, Caesar marched on Roma itself. A second civil war, the great fear of every Roman since the days of Sulla, commenced.

Pompeius Magnus, who had sometimes been Caesar’s ally, led the coalition against him. At the battle of Pharsalus in Greece, Pompeius’s forces were destroyed. Pompeius fled to Egypt, where the minions of the boy-king Ptolemy killed him. They presented his head to Caesar as a gift.

Caesar had circled the Mediterranean, destroying all vestiges of opposition. He set Roma’s subject states in order, confirming the loyalty of their rulers and making them accountable to him alone. Egypt, the great grain producer of the world, remained independent, but Caesar disposed of King Ptolemy and put the boy’s slightly older sister Cleopatra on the throne. Caesar’s relationship with the young queen was both political and personal; Cleopatra was said to have borne him a son. At present, she and the child were residing just outside Roma, on the far side of the Tiber, in a grand house suitable for a visiting head of state.

Caesar’s authority was absolute. Like Sulla before him, he proudly assumed the title of dictator. Unlike Sulla, he showed no inclination ever to lay down his power. To the contrary, he publicly announced his intention to reign as dictator for life. “King” was a forbidden word in Roma, but Caesar was a king in everything but name. He had done away with elections and appointed magistrates for several years to come; his right-hand man Marcus Antonius was serving as consul. The ranks of the Senate, thinned by civil war, had been filled with new members handpicked by Caesar. These new senators included, to the outrage of many, some Gauls, whose loyalty was more to Caesar than to Roma. It was not clear what function the Senate would serve from this time forward, except to approve the decisions of Caesar. He had assigned control of the mint and the public treasury to his own slaves and freedmen. All legislation and all currency were under his control. His personal fortune, acquired over many years of conquest, was immense beyond imagining. Beside him, Roma’s richest men were paupers.

Whatever his title, it had become clear to everyone that Caesar’s triumph signaled the death of the Republic. Roma would no longer be ruled by a Senate of competing equals, but by one man with absolute power over all others, including the power of life and death.

The long civil war had disrupted many traditions. As all power now attached to the dictator-for-life, it was up to him to oversee a return to normalcy. And so, on the Ides of Februarius, Caesar sat on a throne on the Rostra and presided over the Lupercalia.

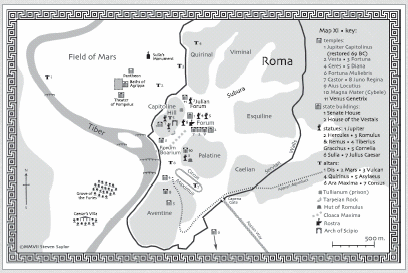

Among the runners assembled in the Forum, stretching their legs and getting ready, was Lucius Pinarius. His grandmother had been the late Julia, one of Caesar’s sisters. His grandfather had been Lucius Pinarius Infelix-“the Unlucky”-so-called, young Lucius had been told, because of his untimely death due to a fall on an icy street. Lucius was seventeen and had run in the Lupercalia before, but he was especially excited to be doing so on this day, with his grand-uncle Gaius presiding.