The city was rebuilt in hurried and often haphazard fashion. Neighbors built across each other’s property lines. New construction often encroached on the public right-of-way, pinching streets into narrow alleys or blocking them altogether. Disputes over property would continue for generations, as would complaints that sewer lines that originally ran under public streets now ran directly under private houses. For centuries to come, visitors to Roma would remark that the general layout of the city more closely resembled a squatters’ settlement than a properly planned city, like those of the Greeks.

The son of Pinaria and Pennatus-who unknowingly carried the patrician bloodlines of both the Pinarii and the Potitii-was duly adopted into the almost equally ancient family of the Fabii. Dorso named the boy Kaeso, and raised him as lovingly as if he had sprung from his own loins. If anything, young Kaeso received greater favor than his siblings, for he was a constant reminder to Dorso of the best days of his own youth. No other time of his life would ever be as special to Dorso as those months of captivity atop the Capitoline, when nothing seemed impossible and every day of survival was a gift from the gods.

Pennatus lived out his life as the loyal slave of Gaius Fabius Dorso. His cleverness and discretion got his master out of many scrapes over the years, often without Dorso ever knowing. Pennatus especially looked after young Kaeso. Friends of the family ascribed Pennatus’s special affection for his young charge to the fact that he had discovered and rescued the foundling. To see the two of them walking across the Palatine, Pennatus doting on the boy and the boy gazing up at the slave with complete trust, was a touching sight.

Pinaria remained a Vestal all her life, though she was plagued by doubts that she kept secret and expressed to no one. Not so secretly, she cherished the gift Pennatus had given her, from which she carefully removed the lead, restoring its golden luster, and which she wore openly after Postumia died and Foslia was made Virgo Maxima. When the other Vestals expressed curiosity, she explained the antiquity of Fascinus without revealing its origin.

Foslia was especially intrigued by the protective qualities of Fascinus. As Virgo Maxima she introduced the practice of incorporating Fascinus into triumphal processions. She had a copy made of Pinaria’s original and placed it out of sight under the chariot of a victorious general, where it served to avert any evil that might be cast by envious eyes. The placement beneath the chariot of this object, called a fascinum, became a traditional duty of the Vestals from that time forward. Similar amulets made of base metals quickly spread into common use. In time, almost every pregnant women in Roma wore her own fascinum to protect her and her baby from malicious spells. Some had wings, but most did not.

Pinaria had become very fond of Dorso during their captivity on the Capitoline. Afterward, she was careful to keep a respectable distance from him, lest their friendship arouse unsavory suspicions. Nevertheless, at public ceremonies their paths frequently crossed. On those occasions, Pinaria sometimes caught glimpses of Pennatus. She avoided looking into his eyes and never spoke to him.

These occasions also allowed Pinaria to see her son at various stages as he grew up. When Kaeso attained his majority and celebrated his sixteenth birthday by donning a man’s toga, no one, including Kaeso, thought it odd that Pinaria should be invited to the celebration. Everyone knew that the Vestal had witnessed his father’s famous walk beyond the barricades, and that his father held her in special esteem.

But young Kaeso was a little surprised when Pinaria asked him to join her alone in the garden. He was still more surprised at the gift she gave him. It was a gold chain upon which hung a gleaming golden amulet of the sort called a fascinum.

Kaeso smiled. With his unruly, straw-colored hair and his bright blue eyes, he still looked like a child to Pinaria. “But I’m not a baby. And I’m certainly not a pregnant woman! I’m a man. That’s the whole point of this day!”

“Even so, I want you to have this. I believe that a primal force-a power older than the gods-accompanied your father and protected him on his famous walk. That force resides in this very amulet.”

“Are you saying that my father wore this when he walked among the Gauls?”

“No, but it was very close to him, nonetheless. Very close! This is no common fascinum, of the sort that anyone can buy in the market for a few coins. This is the first of all such amulets, the original. This is Fascinus, who dwelled in Roma before any other god, even before Jupiter or Hercules.”

Kaeso was a little taken aback. These were odd words, coming from a Vestal. An image of the masculine generator of life was an odd gift to receive from a sacred virgin. Nonetheless, he obediently put the necklace over his head. He examined the amulet. Its edges were worn from time. “It does look very old.”

“It’s ancient-as old as the divine power it represents.”

“But it’s too precious! I can’t accept it from you.”

“You can. You must!” She took his hands and held them tightly. “On this, your sixteenth birthday, I, the Vestal Pinaria, make a gift of Fascinus to you, Kaeso Fabius Dorso. I ask you to wear it on special occasions, and to pass it on, in time, to your own son. Will you do that for me, Kaeso?”

“Of course I will, Vestal. You honor me.”

Both heard a slight noise, and turned to see that the slave Pennatus was watching them from the portico. There was a look on his face such as Kaeso, who had known the slave all his life, had never seen before, an extraordinary expression of mingled sorrow and joy, fulfillment and regret. Confused, Kaeso looked again at the Vestal, and was astounded to see the very same expression on her face.

Pennatus disappeared within the house. Pinaria released Kaeso’s hands and departed in a different direction, leaving him alone in the garden with the amulet she had given him.

Adults were so very mysterious! Kaeso wondered whether he was ready to become one of them, despite the fact that this was his toga day.

THE ARCHITECT OF HIS OWN FORTUNE

312 B.C.

“So, young man, this is your toga day-and what a splendid day for it! Tell me, how have you celebrated so far?”

Surrounded by the magnificent gardens at the center of his magnificent house, wearing his finest toga for the occasion, Quintus Fabius sat with his arms crossed, wrinkled his craggy brow, and appeared to scowl at his visitor. Young Kaeso had been warned about his eminent cousin’s severe expression; Roma’s greatest general was not known for smiling. Kaeso tried not to be intimidated. Even so, he had to clear his throat before he could answer.

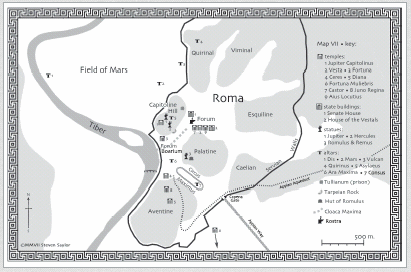

“Well, cousin Quintus, I rose very early. My father presented me with a family heirloom, a golden fascinum on a golden chain, which he took from his own neck to place over mine. There’s a story connected with it; it was given to my grandfather long ago by the famous Vestal Pinaria. Then father presented me with my toga, and helped me put it on. I never imagined it would be so complicated, to make the folds hang correctly! We took a long walk around the Forum, where he introduced me to his friends and colleagues. I was allowed to mount the orator’s platform, to see what the Forum looks like from the perspective of the Rostra.”

“Of course, when I was boy,” said Quintus, interrupting, “the speaker’s platform was not yet called the Rostra, because it hadn’t yet been decorated with all those ships’ beaks. Do you know when that happened?”

Kaeso cleared his throat again. “I believe it was during the consulship of Lucius Furius Camillus, the grandson of the great Camillus. The coastal city of Antium was subdued by Roman arms, and the Antiates were made to remove the ramming prows-the so-called rostra, or ‘beaks’-from their warships, and send them as tribute to Roma. The beaks were installed as decorations on the orator’s platform; hence the platform’s name, the Rostra.”