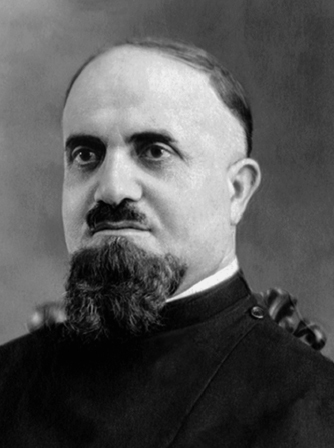

Krikoris Balakian was an Armenian archbishop arrested and deported in the roundup of key Armenians in late April 1915. Balakian managed to escape his caravan and Turkey. He was a star witness at Tehlirian’s trial. (CPA Media / Pictures From History)

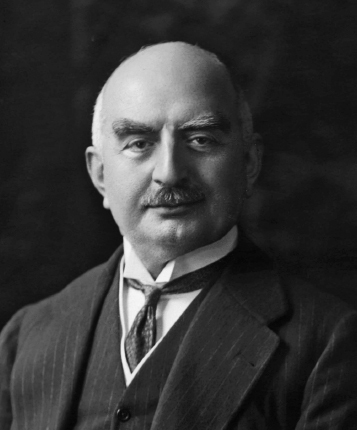

Calouste Gulbenkian was known as “Mr. Five Percent” because this was the commission he demanded for negotiating key oil concessions in the Middle East. Though Britain and other clients fought him in court, Gulbenkian eventually won his case, becoming one of the world’s richest men. (Photo 12 / Polaris)

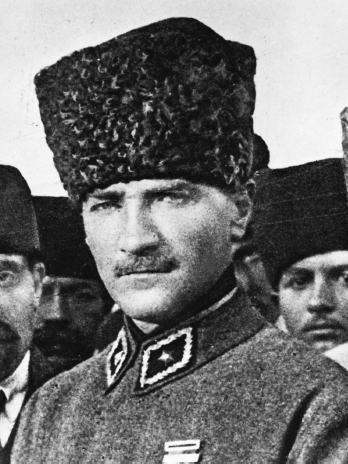

General Mustapha Kemal made his reputation as a bold commander in Gallipoli. At the end of World War I, as Young Turk leaders fled Turkey, Kemal successfully led what remained of the Ottoman army against Greek and Armenian forces, compelling Britain to sharply modify its postwar plans for the Ottoman Empire. Kemal would adopt the name Ataturk as founder of modern Turkey. (The Art Archive at Art Resource, NY)

Aubrey Herbert was a trusted British diplomat tasked with the most challenging assignments. Two weeks before Talat Pasha was assassinated, Scotland Yard requested that Herbert interview the former Ottoman leader in Germany. Herbert was a close acquaintance of some of the most significant “Orientalists” of the period, including T. E. Lawrence and Gertrude Bell. Though barely mentioned in history books, Herbert was a key operator in Near East affairs. (CPA Media / Pictures From History)

Hailed as a hero of the Armenian people, twenty-eight-year-old Soghomon Tehlirian, seen here with his young bride, Anahid, visited Paris in 1924, three years after he assassinated Talat Pasha. (CPA Media / Pictures From History)

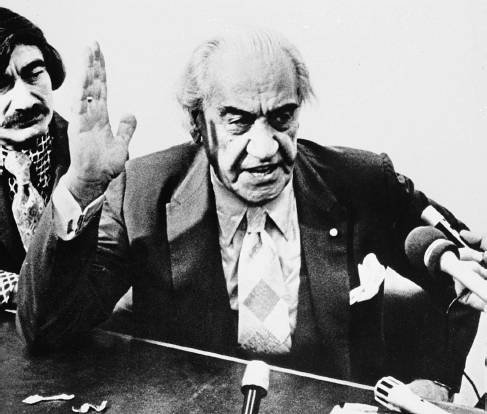

In 1973, Gourgen Yanikian lured two Turkish diplomats to a hotel room in Santa Barbara, California, under the pretense of making a gift to the Republic of Turkey. Yanikian then murdered both men in a self-proclaimed act of revenge in the name of the Armenian Genocide. In a letter to the Los Angeles Times he urged Armenians to wage terror attacks against Turkey. (Associated Press)

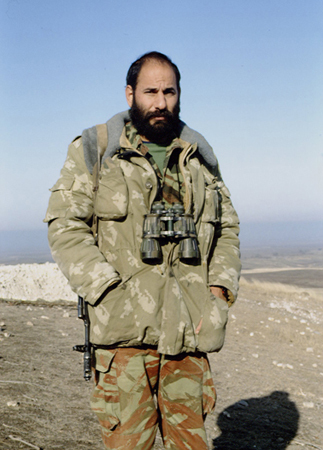

Born in Southern California, Monte Melkonian graduated from UC Berkeley before joining revolutionary efforts in the Middle East. Melkonian would eventually become a member of ASALA, the Armenian organization that committed dozens of acts of terror around the world. After spending three years in French prisons, Melkonian immigrated to Armenia and would become an important commander in the war with Azerbaijan. Melkonian died in battle at only thirty-five years old in 1993. (© Max Sivaslian / Sygma / Corbis)

Talat Pasha’s dress shirt is on display at the Istanbul Military Museum (Askeri Muze) in the “Hall of Armenian Issue with Documents.” A brass plaque explains: “Blood-stained shirt worn by Grand Vizier Talat Pasha when he was assassinated by an Armenian called Sogomon Tehlerian [sic] in Berlin on May [sic] 15th 1921.” The display case is surrounded by photographic documentation of Armenian atrocities against Muslims. (Eric Bogosian)

Hrant Dink was an Armenian Turkish editor of the journal Agos, in which he argued for memorializing the Armenians who died during World War I. He was gunned down outside his Istanbul offices by a young man affiliated with Turkish extremists incensed by Dink’s humanitarian views. At his funeral, thousands of people took to the streets of Istanbul with placards that said “We Are All Armenians” or “We Are All Hrant Dink.” (Associated Press)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First and foremost, I must thank Aram Arkun for his dedication and invaluable guidance during this long journey. Aram provided the translations of Armenian and Turkish which were essential to a full investigation of the story. He was there with an answer to my every question on Armenian and Turkish history and politics. He vetted the manuscript several times. He was there from start to finish. Thank you, Aram.

Thanks to Ted Bogosian and Marc Mamigonian, who made themselves available from the very first with desperately needed informational and emotional support. Thanks to Leslie Peirce for invaluable expertise.

Thanks to those people who shared with me their personal knowledge of Operation Nemesis and Armenian revolutionary activity: Viken Hovsepian, Gerard Libaridian, Marian Mesrobian MacCurdy, Sylva Natali Manoogian, and Melineh Verma.

Thanks to my history-writing coach and buddy Sarah Vowell, who was also ready with strategy and a backslap when the going got rough. Thanks to my old friend Joel Golb, who provided the rock-solid German translation of the Berlin trial and hosted my visit to Berlin. Thanks to Eddy Vicken Noukoujikian for a warm introduction to Armenian Paris. And to all the folks at NAASR.

Special thanks to my agent Simon Green, who was always sure-footed when I was off balance and fully confident was I was ready to scuttle the boat.

Thanks to Geoffrey Shandler, who invited me into the Little, Brown fold and encouraged a more ambitious book. Thank you to Reagan Arthur for believing in this book, to John Parsley for his calm, steadfast presence, and very, very importantly David Sobel, who diligently solved the unsolvable and did not despair when faced with hundreds of pages of disorganized manuscript.

Special thanks to those who provided research and editorial assistance: Annette Vowinckel (Berlin), Dana Vowinckel, Maria Alegre, Ewan Roxbourgh, Liz Seramur at Wyss Photo, Melissa Levine at the University of Michigan, and at Little, Brown, Allie Sommer, Malin von Euler-Hogan, Amanda Heller, Ruth Cross, and Betsy Uhrig. Thanks to the promotion team, Catherine Cullen and Meghan Deans. Thank you to Jeffrey Ward for his impeccable cartography.

When I was in the last draft of the manuscript I was very fortunate to be invited to spend some time at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, as a guest of the Armenian Studies Program. The time I spent there exploring the broader themes with experts in the field was an invaluable aid. Very special thanks to Kathryn Babayan and Ronald Grigor Suny for inviting me. Thanks to Kevork Bardakjian, Melanie Tanielian, and Tamar Boyadjian as well as the postdoctoral fellows who provided much-needed interrogations: Ruken Sengul, Michael Pifer, and Hayarpi Papikyan. Thanks to Zana Kweiser and Michelle Andonian for enlarging my visit to Ann Arbor and Detroit. Finally, special thanks to Fatma Muge Gocek for the long discussions and support.

A number of experts in the fields of Ottoman and Armenian history donated their precious time to answer my questions and engage in naked discussions of the topic. Thank you to Taner Akcam, Anny Bakalian (Middle East and Middle Eastern American Center, CUNY), Peter Balakian, Michael Bobelian, Lerna Ekmekcioglu, Ayda Erbal, Basak Ertur, Ara Ghazarians (Armenian Cultural Foundation), Vartan Gregorian, Christopher Gunn, Rolf Hosfeld (Lepsius Institute, Berlin), Jean Claude Kebabjian (Center for Armenian Diaspora Studies, Paris), Raymond Kevorkian (AGBU Nubarian Library, Paris), Stephen Kinzer, Vartan Matiossian, Khatchig Mouradian (Hairenik), Nora Nercessian, Gregory P. Nowell, Donald Quataert, Verjine Svazlian, Alina and Zareh Tcheknavorian, and Ruth Thomasian (Project SAVE).