My First Book

INTRODUCTION

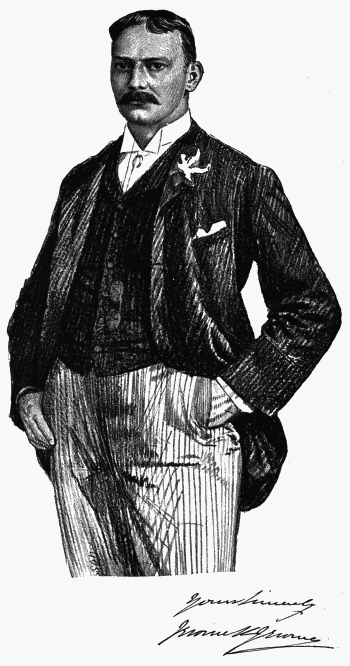

By Jerome K. Jerome

'PLEASE, sir,' he said, 'could you tell me the right time?'

'Twenty minutes to eight,' I replied, looking at my watch.

'Oh,' he remarked. Then added for my information after a pause: 'I haven't got to be in till half-past eight.'

After that we fell back into our former silence, and sat watching the murky twilight, he at his end of the park seat, I at mine.

'And do you live far away?' I asked, lest, he having miscalculated, the short legs might be hard put to it.

'Oh no, only over there,' he answered, indicating with a sweep of his arm the northern half of London where it lay darkening behind the chimney-fringed horizon; 'I often come and sit here.'

It seemed an odd pastime for so very small a citizen. 'And what makes you like to come and sit here?' I said.

'Oh, I don't know,' he replied, 'I think.'

'And what do you think about?'

'Oh—oh, lots of things.'

He inspected me shyly out of the corner of his eye, but, satisfied apparently by the scrutiny, he sidled up a little nearer.

'Mama does not like this evening time,' he confided to me; 'it always makes her cry. But then,' he went on to explain, 'Mama has had a lot of trouble, and that makes anyone feel different about things, you know.'

I agreed that this was so. 'And do you like this evening time?' I enquired.

'Yes,' he answered; 'don't you?'

'Yes, I like it too,' I admitted. 'But tell me why you like it, then I will tell you why I like it.'

'Oh,' he replied, 'things come to you.'

'What things?' I asked.

Again his critical eye passed over me, and it raised me in my own conceit to find that again the inspection contented him, he evidently feeling satisfied that here was a man to whom another gentleman might speak openly and without reserve.

He wriggled sideways, slipping his hands beneath him and sitting on them.

'Oh, fancies,' he explained; 'I'm going to be an author when I grow up, and write books.'

Then I knew why it was that the sight of his little figure had drawn me out of my path to sit beside him, and why the little serious face had seemed so familiar to me, as of some one I had once known long ago.

So we talked of books and bookmen. He told me how, having been born on the fourteenth of February, his name had come to be Valentine, though privileged parties, as for example Aunt Emma, and Mr. Dawson, and Cousin Naomi, had shortened it to Val, and Mama would sometimes call him Pickaniny, but that was only when they were quite alone. In return I confided to him my name, and discovered that he had never heard it, which pained me for the moment, until I found that of all my confreres, excepting only Mr. Stevenson, he was equally ignorant, he having lived with the heroes and the heroines of the past, the new man and the new woman, the new pathos and the new humour being alike unknown to him.

Scott and Dumas and Victor Hugo were his favourites. 'Gulliver's Travels,' 'Robinson Crusoe,' 'Don Quixote,' and the 'Arabian Nights,' he knew almost by heart, and these we discussed, exchanging many pleasant and profitable ideas upon the same. But the psychological novel, I gathered, was not to his taste. He liked 'real stories,' he told me, naively unconscious of the satire, 'where people did things.'

'I used to read silly stuff once,' he confessed humbly, 'Indian tales and that sort of thing, you know, but Mama said I'd never be able to write if I read that rubbish.'

'So you gave it up,' I concluded for him.

'Yes,' he answered. But a little sigh of regret, I thought, escaped him at the same time.

'And what do you read now?' I asked.

'I'm reading Marlowe's plays and De Quincey's Confessions (he called him Quinsy) just now,' was his reply.

'And do you understand them?' I queried.

'Fairly well,' he answered. Then added more hopefully, 'Mama says I'll get to like them better as I go on.'

'I want to learn to write very, very well indeed,' he suddenly added after a long pause, his little earnest face growing still more serious, 'then I'll be able to earn heaps of money.'

It rose to my lips to answer him that it was not always the books written very, very well that brought in the biggest heaps of money; that if heaps of money were his chiefest hope he would be better advised to devote his energies to the glorious art of self-advertisement and the gentle craft of making friends upon the Press. But something about the almost baby face beside me, fringed by the gathering shadows, silenced my middle-aged cynicism. Involuntarily my gaze followed his across the strip of foot-worn grass, across the dismal-looking patch of ornamental water, beyond the haze of tangled trees, beyond the distant row of stuccoed houses, and, arrived there with him, I noticed many men and women clothed in the garments of all ages and all lands, men and women who had written very, very well indeed and who notwithstanding had earned heaps of money, the hire worthy of the labourer, and who were not ashamed; men and women who had written true words which the common people had read gladly; men and women who had been raised to lasting fame upon the plaudits of their day; and before the silent faces of these, made beautiful by Time, the little bitter sneers I had counted truth rang foolish in my heart, so that I returned with my young friend to our green seat beside the foot-worn grass, feeling by no means so sure as when I had started which of us twain were the better fitted to teach wisdom to the other.

'And what would you do, Valentine, with heaps of money?' I asked.

Again for a moment his old shyness of me returned. Perhaps it was not quite a legitimate question from a friend of such recent standing. But his frankness wrestled with his reserve and once more conquered.

'Mama need not do any work then,' he answered. 'She isn't really strong enough for it, you know,' he explained, 'and I'd buy back the big house where she used to live when she was a little girl, and take her back to live in the country—the country air is so much better for her, you know—and Aunt Emma, too.'

But I confess that as regards Aunt Emma his tone was not enthusiastic.

I spoke to him—less dogmatically than I might have done a few minutes previously, and I trust not discouragingly—of the trials and troubles of the literary career, and of the difficulties and disappointments awaiting the literary aspirant, but my croakings terrified him not.

'Mama says that every work worth doing is difficult,' he replied, 'and that it doesn't matter what career we choose there are difficulties and disappointments to be overcome, and that I must work very hard and say to myself "I will succeed," and then in the end, you know, I shall.'

'Though of course it may be a long time,' he added cheerfully.

Only one thing in the slightest daunted him, and that was the weakness of his spelling.

'And I suppose,' he asked, 'you must spell very well indeed to be an author.'

I explained to him, however, that this failing was generally met by a little judicious indistinctness of caligraphy, and all obstacles thus removed, the business of a literary gent seemed to him an exceptionally pleasant and joyous one.

'Mama says it is a noble calling,' he confided to me, 'and that anyone ought to be very proud and glad to be able to write books, because they give people happiness and make them forget things, and that one ought to be awfully good if one's going to be an author, so as to be worthy to help and teach others.'

'And do you try to be awfully good, Valentine?' I enquired.