But this brings me to the most extraordinary feature of this singular demonstration. I do not think that the publishers were at all troubled by it; I cannot conscientiously say that I was; I have every reason to believe that the poets themselves, in and out of the volume, were not displeased at the notoriety they had not expected, and I have long since been convinced that my most remorseless critics were not in earnest, but were obeying some sudden impulse started by the first attacking journal. The extravagance of the Red Dog Jay Hawk was emulated by others: it was a large, contagious joke, passed from journal to journal in a peculiar cyclonic Western fashion. And there still lingers, not unpleasantly, in my memory the conclusion of a cheerfully scathing review of the book which may make my meaning clearer: 'If we have said anything in this article which might cause a single pang to the poetically sensitive nature of the youthful individual calling himself Mr. Francis Bret Harte—but who, we believe, occasionally parts his name and his hair in the middle—we will feel that we have not laboured in vain, and are ready to sing Nunc Dimittis, and hand in our checks. We have no doubt of the absolutely pellucid and lacteal purity of Franky's intentions. He means well to the Pacific Coast, and we return the compliment. But he has strayed away from his parents and guardians while he was too fresh. He will not keep without a little salt.'

It was thirty years ago. The book and its Rabelaisian criticisms have been long since forgotten. Alas! I fear that even the capacity for that Gargantuan laughter which met them, in those days, exists no longer. The names I have used are necessarily fictitious, but where I have been obliged to quote the criticisms from memory I have, I believe, only softened their asperity. I do not know that this story has any moral. The criticisms here recorded never hurt a reputation nor repressed a single honest aspiration. A few contributors to the volume, who were of original merit, have made their mark, independently of it or its critics. The editor, who was for two months the most abused man on the Pacific slope, within the year became the editor of its first successful magazine. Even the publisher prospered, and died respected!

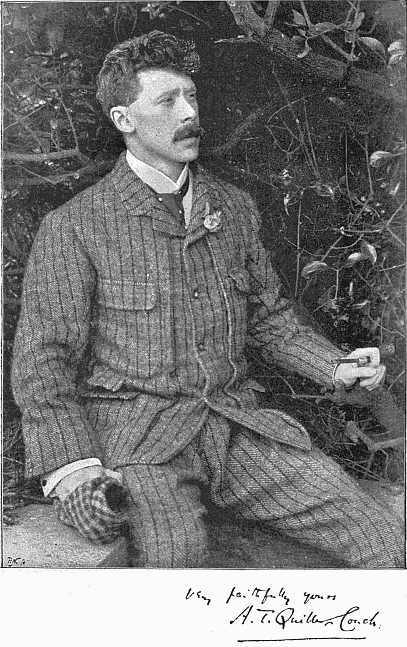

'DEAD MAN'S ROCK'

By 'Q.'

I CHERISH no parental illusions about 'Dead Man's Rock.' It is two or three years since I read a page of that blood-thirsty romance, and my only copy of it was found, the other day, in turning out the lumber-room at the top of the house. Later editions have been allowed to appear with all the inaccuracies and crudities of the first. On page 116, Bombay is still situated in the Bay of Bengal, and may continue to adorn that shore. The error must be amusing, since unknown friends continue to write and confess themselves tickled by it; and it is stupid to begin amending a book in which you have lost interest. But though this is my attitude towards 'Dead Man's Rock,' I can still look back on the writing of it as on an amusing adventure.

It was begun in the late summer of 1886, and was my first attempt at telling a story on paper. I am careful to say 'on paper,' because in childhood I was telling myself stories from morning to night. Tens of thousands of small boys are doing the same every day in the year; but I should be sorry to guess how much of my time, between the ages of seven and thirteen, must have been given up to weaving these childish epics. They were curious jumbles; the characters (of which I had a constant set) being drawn indiscriminately from the 'Morte d'Arthur,' 'Bunyan's Holy War,' 'Pope's Iliad,' 'Ivanhoe,' and a book of Fairy Tales by Holme Lee, as well as from history; and the themes ranging from battles and tournaments to cricket, wrestling, and sailing matches. Anachronisms never troubled the story-teller. The Duke of Wellington would cheerfully break a lance with Captain Credence or Tristram of Lyonesse, and I rarely made up a football fifteen without including Hardicanute (whom I loved for his name), Hector (dear for his own sake) and Wamba (who supplied the comic interest and scored off Thersites). They were brave companions; but at the age of thirteen they deserted me suddenly. Or perhaps after reading Mr. Stevenson's 'Chapter on Dreams,' I had better say it was the Piskies—the Small People—who deserted me. They alone know why—for their pensioner had never betrayed a single one of their secrets—or why in these later times, when he sells their confidences for money, they have come back to help him, though more sparingly. Three or four of the little stories in 'Noughts and Crosses' are but translated dreams, and there are others in my notebook; but now I never compose without some pain, whereas in the old days I had but to sit alone in a corner or take a solitary walk and invite them, and they did all the work. But one summer evening I summoned them and met with no response. Without warning the tales had come to an end.

From my first school at Newton Abbot I went to Clifton, and from Clifton in my nineteenth year to Oxford. It was here that the old desire to weave stories began to come back. Mr. Stevenson's 'Treasure Island' was the immediate cause. I had been scribbling all through my school days; had written a prodigious quantity of bad reflective poetry and burnt it as soon as I really began to reflect; and was now plying the Oxford Magazine with light verse, a large proportion of which was lately reprinted in a thin volume, with the title of 'Green Bays.' But I wrote little or no prose. My prose essays at school were execrable. I had followed after false models for a while, and when gently made aware of this by the sound and kindly scholar who looked over our sixth-form essays at Clifton, had turned dispirited and wrote scarcely at all. Though reading great quantities of fiction, I had, as has been said, no thought of telling a story, and so far as I knew, no faculty. The desire, at least, was awakened by 'Treasure Island,' and, in explanation of this, I can only quote the gentleman who reviewed my first book in the Athen?um, and observed that 'great wits jump, and lesser wits jump with them.' That is just the truth of it. I began as a pupil and imitator of Mr. Stevenson, and was lucky in my choice of a master.

The germ of 'Dead Man's Rock' was a curious little bit of family lore, which I may extract from my father's history of Polperro, a small haven on the Cornish coast. The Richard Quiller of whom he speaks is my great grandfather.

'In the old home of the Quillers, at Polperro, there was hanging on a beam a key, which we as children regarded with respect and awe, and never dared to touch, for Richard Quiller had put the key of his quadrant on a nail, with strong injunctions that no one should take it off until his return (which never happened), and there, I believe, it still hangs. His brother John served for several years as commander of a hired armed lugger, employed in carrying despatches in the French war, Richard accompanying him as subordinate officer. They were engaged in the inglorious bombardment of Flushing in 1809. Some short time after this they were taken, after a desperate fight with a pirate, into Algiers, but were liberated on the severe remonstrances of the British Consul. They returned to their homes in most miserable plight, having lost their all, except their Bible, much valued then by the unfortunate sailors, and now by a descendant in whose possession it is. About the year 1812 these same brothers sailed to the island of Teneriffe in an armed merchant ship, but after leaving that place were never heard of.'