This is the history of how I drifted into the writing of books. If it saves one beginner so inexperienced and unfriended as I was in those days from putting his hand to a 'hanging' agreement under any circumstances whatsoever, it will not have been set out in vain.

The advice that I give to would-be authors, if I may presume to offer it, is to think for a long while before they enter at all upon a career so hard and hazardous, but having entered on it, not to be easily cast down. There are great virtues in perseverance, even though critics sneer and publishers prove unkind.

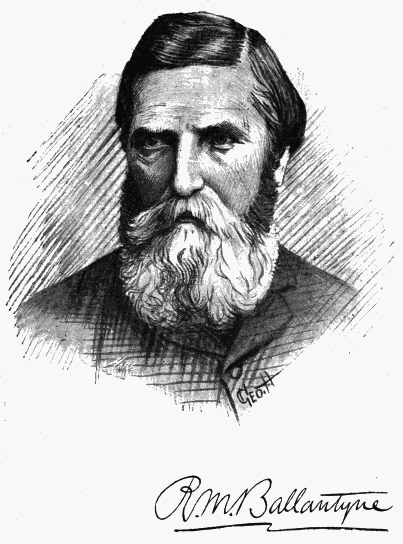

'HUDSON'S BAY'

By R. M. Ballantyne

HAVING been asked to give some account of the commencement of my literary career, I begin by remarking that my first book was not a tale or 'story-book,' but a free-and-easy record of personal adventure and every-day life in those wild regions of North America which are known, variously, as Rupert's Land—The Hudson's Bay Territory—The Nor' West, and 'The Great Lone Land.'

The record was never meant to see the light in the form of a book. It was written solely for the eye of my mother, but, as it may be said that it was the means of leading me ultimately into the path of my life-work, and was penned under somewhat peculiar circumstances, it may not be out of place to refer to it particularly here.

The circumstances were as follows:—

After having spent about six years in the wild Nor' West, as a servant of the Hudson's Bay Fur Company, I found myself, one summer—at the advanced age of twenty-two—in charge of an outpost on the uninhabited northern shores of the Gulf of St. Lawrence named Seven Islands. It was a dreary, desolate spot; at that time far beyond the bounds of civilisation. The gulf, just opposite the establishment, was about fifty miles broad. The ships which passed up and down it were invisible, not only on account of distance, but because of seven islands at the mouth of the bay coming between them and the outpost. My next neighbour, in command of a similar post up the gulf, was about seventy miles distant. The nearest house down the gulf was about eighty miles off, and behind us lay the virgin forests, with swamps, lakes, prairies, and mountains, stretching away without break right across the continent to the Pacific Ocean.

The outpost—which, in virtue of a ship's carronade and a flagstaff, was occasionally styled a 'fort'—consisted of four wooden buildings. One of these—the largest, with a verandah—was the Residency. There was an offshoot in rear which served as a kitchen. The other houses were a store for goods wherewith to carry on trade with the Indians, a stable, and a workshop. The whole population of the establishment—indeed of the surrounding district—consisted of myself and one man—also a horse! The horse occupied the stable, I dwelt in the Residency, the rest of the population lived in the kitchen.

There were, indeed, five other men belonging to the establishment, but these did not affect its desolation, for they were away netting salmon at a river about twenty miles distant at the time I write of.

My 'Friday'—who was a French-Canadian—being cook, as well as man-of-all-works, found a little occupation in attending to the duties of his office, but the unfortunate Governor had nothing whatever to do except await the arrival of Indians, who were not due at that time. The horse was a bad one, without a saddle, and in possession of a pronounced backbone. My 'Friday' was not sociable. I had no books, no newspapers, no magazines or literature of any kind, no game to shoot, no boat wherewith to prosecute fishing in the bay, and no prospect of seeing anyone to speak to for weeks, if not months, to come. But I had pen and ink, and, by great good fortune, was in possession of a blank paper book fully an inch thick.

These, then, were the circumstances in which I began my first book.

When that book was finished, and, not long afterwards, submitted to the—I need hardly say favourable—criticism of my mother, I had not the most distant idea of taking to authorship as a profession. Even when a printer-cousin, seeing the MS., offered to print it, and the well-known Blackwood of Edinburgh, seeing the book, offered to publish it—and did publish it—my ambition was still so absolutely asleep that I did not again put pen to paper in that way for eight years thereafter, although I might have been encouraged thereto by the fact that this first book—named 'Hudson's Bay'—besides being a commercial success, received favourable notice from the Press.

It was not until the year 1854 that my literary path was opened up. At that time I was a partner in the late publishing firm of Constable & Co., of Edinburgh. Happening one day to meet with the late William Nelson, publisher, I was asked by him how I should like the idea of taking to literature as a profession. My answer I forget. It must have been vague, for I had never thought of the subject before.

'Well,' said he, 'what would you think of trying to write a story?'

Somewhat amused, I replied that I did not know what to think, but I would try if he wished me to do so.

'Do so,' said he, 'and go to work at once'—or words to that effect.

I went to work at once, and wrote my first story or work of fiction. It was published in 1855 under the name of 'Snowflakes and Sunbeams; or, The Young Fur-traders.' Afterwards the first part of the title was dropped, and the book is now known as 'The Young Fur-traders.' From that day to this I have lived by making story-books for young folk.

From what I have said it will be seen that I have never aimed at the achieving of this position, and I hope that it is not presumptuous in me to think—and to derive much comfort from the thought—that God led me into the particular path along which I have walked for so many years.

The scene of my first story was naturally laid in those backwoods with which I was familiar, and the story itself was founded on the adventures and experiences of myself and my companions. When a second book was required of me, I stuck to the same regions, but changed the locality. When casting about in my mind for a suitable subject, I happened to meet with an old retired 'Nor'wester' who had spent an adventurous life in Rupert's Land. Among other duties he had been sent to establish an outpost of the Hudson's Bay Company at Ungava Bay, one of the most dreary parts of a desolate region. On hearing what I wanted he sat down and wrote a long narrative of his proceedings there, which he placed at my disposal, and thus furnished me with the foundation of 'Ungava.'

But now I had reached the end of my tether, and when a third story was wanted I was compelled to seek new fields of adventure in the books of travellers. Regarding the Southern seas as a most romantic part of the world—after the backwoods!—I mentally and spiritually plunged into those warm waters, and the dive resulted in the 'Coral Island.'

It now began to be borne in upon me that there was something not quite satisfactory in describing, expatiating on, and energising in, regions which one has never seen. For one thing, it was needful to be always carefully on the watch to avoid falling into mistakes—geographical, topographical, natural-historical, and otherwise.

6

This and the succeeding illustrations are from photographs by Fradelle & Young.