One writer—the greatest enemy I have ever had, though I exonerate him of all but thoughtlessness—wrote me down a 'humourist,' which term of reproach (as it is considered to be in Merrie England) has clung to me ever since, so that now, if I pen a pathetic story, the reviewer calls it 'depressing humour,' and if I tell a tragic story, he says it is 'false humour,' and, quoting the dying speech of the broken-hearted heroine, indignantly demands to know 'where he is supposed to laugh.' I am firmly persuaded that if I committed a murder half the book reviewers would allude to it as a melancholy example of the extreme lengths to which the 'new humour' had descended.

'Once a humourist, always a humourist,' is the reviewer's motto.

'And all things allowed for—the unenthusiastic publisher, the insufficiently appreciative public, the wicked critic,' says my little pink friend, breaking his somewhat long silence, 'what do you think of literature as a profession?'

I take some time to reply, for I wish to get down to what I really think, not stopping, as one generally does, at what one thinks one ought to think.

'I think,' I begin, at length, 'that it depends upon the literary man. If a man think to use literature merely as a means to fame and fortune, then he will find it an extremely unsatisfactory profession, and he would have done better to take up politics or company promoting. If he trouble himself about his status and position therein, loving the uppermost tables at feasts, and the chief seats in public places, and greetings in the markets, and to be called of men, Master, Master, then he will find it a profession fuller than most professions of petty jealousy, of little spite, of foolish hating and foolish log-rolling, of feminine narrowness and childish querulousness. If he think too much of his prices per thousand words, he will find it a degrading profession; as the solicitor, thinking only of his bills-of-cost, will find the law degrading; as the doctor, working only for two-guinea fees, will find medicine degrading; as the priest, with his eyes ever fixed on the bishop's mitre, will find Christianity degrading.

'But if he love his work for the work's sake, if he remain child enough to be fascinated with his own fancies, to laugh at his own jests, to grieve at his own pathos, to weep at his own tragedy—then, as, smoking his pipe, he watches the shadows of his brain coming and going before his half-closed eyes, listens to their voices in the air about him, he will thank God for making him a literary man. To such a one, it seems to me, literature must prove ennobling. Of all professions it is the one compelling a man to use whatever brain he has to its fullest and widest. With one or two other callings, it invites him—nay, compels him—to turn from the clamour of the passing day to speak for a while with the voices that are eternal.

'To me it seems that if anything outside oneself can help one, the service of literature must strengthen and purify a man. Thinking of his heroine's failings, of his villain's virtues, may he not grow more tolerant of all things, kinder thinking towards man and woman? From the sorrow that he dreams, may he not learn sympathy with the sorrow that he sees? May not his own brave puppets teach him how a man should live and die?

'To the literary man, all life is a book. The sparrow on the telegraph wire chirps cheeky nonsense to him as he passes by. The urchin's face beneath the gas lamp tells him a story, sometimes merry, sometimes sad. Fog and sunshine have their voices for him.

'Nor can I see, even from the most worldly and business-like point of view, that the modern man of letters has cause of complaint. The old Grub Street days when he starved or begged are gone. Thanks to the men who have braved sneers and misrepresentation in unthanked championship of his plain rights, he is now in a position of dignified independence; and if he cannot attain to the twenty thousand a year prizes of the fashionable Q.C. or M.D., he does not have to wait their time for his success, while what he can and does earn is amply sufficient for all that a man of sense need desire. His calling is a password into all ranks. In all circles he is honoured. He enjoys the luxury of a power and influence that many a prime minister might envy.

'There is still a last prize in the gift of literature that needs no sentimentalist to appreciate. In a drawer of my desk lies a pile of letters, of which if I were not very proud I should be something more or less than human. They have come to me from the uttermost parts of the earth, from the streets near at hand. Some are penned in the stiff phraseology taught when old fashions were new, some in the free and easy colloquialism of the rising generation. Some, written on sick beds, are scrawled in pencil. Some, written by hands unfamiliar with the English language, are weirdly constructed. Some are crested, some are smeared. Some are learned, some are ill-spelled. In different ways they tell me that, here and there, I have brought to some one a smile or pleasant thought; that to some one in pain and in sorrow I have given a moment's laugh.'

Pinky yawns (or a shadow thrown by the guttering candle makes it seem so). 'Well,' he says, 'are we finished? Have we talked about ourselves, glorified our profession, and annihilated our enemies to our entire satisfaction? Because, if so, you might put me back. I'm feeling sleepy.'

I reach out my hand, and take him up by his wide, flat waist. As I draw him towards me, his little legs vanish into his squat body, the twinkling eye becomes dull and lifeless. The dawn steals in upon him, for I have sat working long into the night, and I see that he is only a little shilling book bound in pink paper. Wondering whether our talk together has been as good as at the time I thought it, or whether he has led me into making a fool of myself, I replace him in his corner.

'CAVALRY LIFE'

By 'John Strange Winter'

(Mrs. Arthur Stannard)

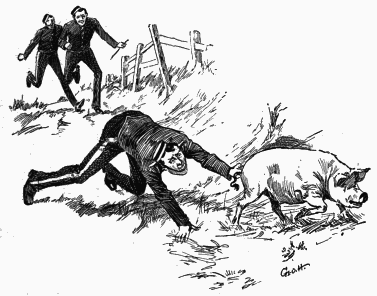

MY first book 'as ever was' was written, or, to speak quite correctly, was printed, on the nursery floor some thirty odd years ago. I remember the making of the book very well; the leaves were made from an old copybook, and the back was a piece of stiff paper, sewed in place and carefully cut down to the right size. So far as I remember, it was about three soldiers and a pig. I don't quite know how the pig came in, but that is a mere detail. I have no data to go upon (as I did not dream thirty years ago that I should ever be so known to fame as to be asked to write the true history of my first book), but I have a wonderful memory, and to the best of my recollection it was, as I say, about three soldiers and a pig.

It never saw the light, and there are times when I feel thankful to a gracious Providence that I have been spared the power of gratifying the temptation to give birth to those early efforts, after the manner of Sir Edwin Landseer and that pathetic little childish drawing of two sheep, which is to be seen at provincial exhibitions of pictures, for the encouragement and example of the rising generation.

So far as I can recall, I made no efforts for some years to woo fickle fortune after the attempt to recount the story of the three soldiers and a pig; but when I was about fourteen my heart was fired by the example of a schoolfellow, one Josephine H——, who spent a large portion of her time writing stories, or, as our schoolmistress put it, wasting time and spoiling paper. All the same, Josephine H—— 's stories were very good, and I have often wondered since those days whether she, in after life, went on with her favourite pursuits. I have never heard of her again except once, and then somebody told me that she had married a clergyman, and lived at West Hartlepool. Yes, all this has something to do, and very materially, with the story of my first book. For in emulating Josephine H——, whom I was very fond of, and whom I admired immensely, I discovered that I could write myself, or at least that I wanted to write, and that I had ideas that I wanted to see on paper. Without that gentle stimulant, however, I might never have found out that I might one day be able to do something in the same way myself.