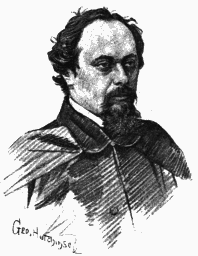

Perhaps it was not all pleasure, so far as I was concerned, but certainly it was all profit. The novels we read were 'Tom Jones,' in four volumes, and 'Clarissa,' in its original eight, one or two of Smollett's, and some of Scott's. Rossetti had not, I think, been a great reader of fiction, but his critical judgment was in some respects the surest and soundest I have known. He was one of the only two men I have ever met with who have given me in personal intercourse a sense of the presence of a gift that is above and apart from talent—in a word, of genius. Nothing escaped him. His alert mind seized upon everything. He had never before, I think, given any thought to fiction as an art, but his intellect played over it like a bright light. It amazes me now, after ten years' close study of the methods of story-telling, to recall the general principles which he seemed to formulate out of the back of his head for the defence of his swift verdicts. 'Now why?' I would say, when the art of the novelist seemed to me to fail, or when the poet's condemnation appeared extreme. 'Because so-and-so must happen,' he would answer. He was always right. He grasped with masterly strength the operation of the two fundamental factors in the novelist's art—the sympathy and the 'tragic mischief.' If these were not working well, he knew by the end of the first chapters that, however fine in observation, or racy in humour, or true in pathos, the work as an organism must fail.

It was an education in literary art to sharpen one's wits on such a grindstone, to clarify one's thought in such a stream, to strengthen one's imagination by contact with a mind that was 'of imagination all compact.'

Now, down to that time, though I had often aspired to the writing of plays, it had never occurred to me that I might write a novel. But I began to think of it then as a remote possibility, and the immediate surroundings of our daily life brought back recollection of the old Cumberland legend. I told the story to Rossetti, and he was impressed by it, but he strongly advised me not to tackle it. The incident did not repel him by its ghastliness, but he saw no way of getting sympathy into it on any side. His judgment disheartened me, and I let the idea go back to the dark chambers of memory. He urged me to try my hand at a Manx story. '"The Bard of Manxland"—it's worth while to be that,' he said—he did not know the author of 'Foc's'le Yarns.' I thought so, too, but the Cumbrian 'statesman' had begun to lay hold of my imagination. I had been reviving my recollection and sharpening my practice of the Cumbrian dialect which had been familiar to my ear, and even to my tongue, in childhood, and so my Manx ambitions had to wait.

Two years passed, the poet died, I had spent eighteen months in daily journalism in London, and was then settled in a little bungalow of three rooms in a garden near the beach at Sandown in the Isle of Wight. And there, at length, I began to write my first novel. I had grown impatient of critical work, had persuaded myself (no doubt wrongly) that nobody would go on writing about other people's writing who could do original writing himself, and was resolved to live on little and earn nothing, and never go back to London until I had written something of some sort. As nearly as I can remember, I had enough to keep things going for four months, and if, at the end of that time, nothing had got itself done, I must go back bankrupt.

Something did get done, but at a heavy price of labour and heart-burning. When I began to think of a theme, I found four or five subjects clamouring for acceptance. There was the story of the Prodigal Son, which afterwards became 'The Deemster'; the story of Jacob and Esau, which in the same way turned into 'The Bondman'; the story of Samuel and Eli, which, after a fashion, moulded itself ultimately into 'The Scapegoat'; and half-a-dozen other stories, chiefly Biblical, which are still on the forehead of my time to come. But the Cumbrian legend was first favourite, and to that I addressed myself. I thought I had seen a way to meet Rossetti's objection. The sympathy was to be got out of the elder son. He was to think God's hand was upon him. But whom God's hand rested on had God at his right hand; so the elder son was to be a splendid fellow—brave, strong, calm, patient, long-suffering, a victim of unrequited love, a man standing square on his legs against all weathers. It is said that the young novelist usually begins with a glorified version of his own character; but it must interest my friends to see how every quality of my first hero was a rebuke to my own peculiar infirmities.

Above this central figure and legendary incident I grouped a family of characters. They were heroic and eccentric, good and bad, but they all operated upon the hero. Then I began to write.

Shall I ever forget the agony of the first efforts? There was the ground to clear with necessary explanations. This I did in the way of Scott in a long prefatory chapter. Having written it I read it aloud, and found it unutterably slow and dead. Twenty pages were gone, and the interest was not touched. Throwing the chapter aside I began with an alehouse scene, intending to work back to the history in a piece of retrospective writing. The alehouse was better, but to try its quality I read it aloud, after the 'Rainbow' scene in 'Silas Marner,' and then cast it aside in despair. A third time I began, and when the alehouse looked tolerable the retrospective chapter that followed it seemed flat and poor. How to begin by gripping the interest, how to tell all and yet never stop the action—these were agonising difficulties.

It took me nearly a fortnight to start that novel, sweating drops as of blood at every fresh attempt. I must have written the first half volume four times at the least. After that I saw the way clearer, and got on faster. At the end of three months I had written nearly two volumes, and then in good spirits I went up to London.

My first visit was to J. S. Cotton, an old friend, and to him I detailed the lines of my story. His rapid mind saw a new opportunity. 'You want peine forte et dure,' he said. 'What's that?' I said. 'An old punishment—a beautiful thing,' he answered. 'Where's my dear old Blackstone?' and the statute concerning the punishment for standing mute was read to me. It was just the thing I wanted for my hero, and I was in rapture, but I was also in despair. To work this fresh interest into my theme, half of what I had written would need to be destroyed!

It was destroyed, the interesting piece of ancient jurisprudence took a leading place in my scheme, and after two months more I got well into the third volume. Then I took my work down to Liverpool, and showed it to my friend, the late John Lovell, a most able man, first manager of the Press Association, but then editing the local Mercury. After he had read it he said, 'I suppose you want my candid opinion?' 'Well, ye—s,' I said. 'It's crude,' he said. 'But it only wants sub-editing.' Sub-editing!

I took it back to London, began again at the first line, and wrote every page over again. At the end of another month the story had been reconstructed, and was shorter by some fifty pages of manuscript. It had drawn my heart's blood to cut out my pet passages, but they were gone, and I knew the book was better. After that I went on to the end and finished with a tragedy. Then the story was sent back to Lovell, and I waited for his verdict.