Stay—I will go upstairs to my lumber room, I will open that box, I will dig deep down among the buried memories of the past, and I will find that book, and I will summon up my courage and ask the publishers of this volume to kindly allow the cover of that book to be reproduced here. It is only by looking at it as I looked at it that you will thoroughly appreciate my feelings on the subject.

I have found the box, but my heart sinks within me as I try to open the lid. All my lost youth lies there. The key is rusty and will hardly turn in the lock.

So—so—so, at last! Ghosts of the long ago, come forth from your resting-places and haunt me once again.

Dear me! dear me! how musty everything smells; how old, and worn, and time-stained everything is. A folded poster:

'Grecian Theatre'

'Mr. G. R. Sims will positively not appear this evening at the entertainment held in the Hall.'

Yes, I remember. I had been announced, entirely without my consent or knowledge, to appear at a hall attached to the Grecian Theatre with Mrs. Georgina Weldon, and take part in an entertainment. This notice was stuck about outside the theatre in consequence of my indignant remonstrance. My old friend Mr. George Conquest had, I need hardly say, nothing to do with that bill. Some one had taken the hall for a special occasion. I think it was something remotely connected with lunatics.

My first play! Poor little play—a burlesque written for my brothers and sisters, and played by us in the Theatre Royal Day Nursery. There were some really brilliant lines in it, I remember. They were taken bodily from a burlesque of H. J. Byron's, which I purchased at Lacy & Son's (now French's) in the Strand—'a new and original burlesque by Master G. R. Sims.' My misguided parents actually had the playbill printed and invited friends to witness the performance. They little knew what they were doing by pandering to my boyish vanity in such a way. But for that printed playbill, and that public performance in my nursery, I might never have taken to the stage, and inflicted upon a long-suffering public Adelphi melodrama and Gaiety burlesque, farcical comedy and comic opera; I might have remained all my life an honest, hard-working City man, relieving my feelings occasionally by joining in the autumn discussions in the Daily Telegraph. I was still in the City when my first book was published. I used, in those days, to get to the City at nine and leave it at six, but I had a dinner hour, and in that dinner hour I wrote short stories and little things that I fancied were funny, and I used to put them in big envelopes and send them to the different magazines. I sent about twenty out in that way. I never had one accepted, but several returned.

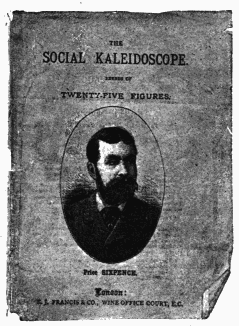

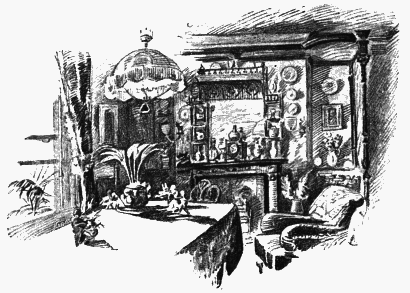

I wrote my first book in my dinner hour, in a City office. I have just found it. Here is the cover. You will observe that it has my portrait on it. I look very ill and thin and haggard. That was, perhaps, the result of going without my dinner in order to devote myself to 'literature.'

If you could look inside that book, if you could see the paper on which it is printed, you would understand the shock it was to me when they laid it in my arms and said: 'Behold your firstborn.'

All the vanity in me (and they tell me that I have a good deal) rose up as I gazed at the battered wreck upon the cover—the man with the face that suggested a prompt subscription to a burial club.

But I shouldn't have minded that so much if the people who bought my book hadn't written to me personally to complain. One gentleman sent me a postcard to say that his volume fell to pieces while he was carrying it home. Another assured me that he had picked enough pieces of straw out of the leaves to make a bed for his horse with, and a third returned a copy to me without paying the postage, and asked me kindly to put it in my dustbin, because his cook was rather proud of the one he had in his back garden.

Still the book sold (the sketches had all previously appeared in the Weekly Dispatch), and when the first edition was exhausted, a new and better one was prepared (without that haggard face upon the cover), and I was happy.

The sale ran into thirty thousand the first year of publication, and as I was fortunate enough to have published it on a royalty, I am glad to say it is still selling.

'The Social Kaleidoscope' was my first book. With it I made my actual debut between covers.

I hadn't done very well before then; since then I have, from a worldly point of view, done remarkably well—far better than I deserved to do, my good-natured friends assure me, and I cordially agree with them.

But I had made a good fight for it, and I had suffered years of disappointment and rebuff. I began to send contributions to periodicals when I was fourteen years old, and a boy at Hanwell College. Fun was the first journal I favoured with my effusions, and week after week I had a sinking at the heart as I bought that popular periodical and searched in vain for my comic verses, my humorous sketches, and my smart paragraphs.

It took me thirteen years to get something printed and paid for, but I succeeded at last, and it was Fun, my early love, that first took me by the hand. When I was on the staff of Fun, and its columns were open to me for all I cared to write, I used often to look over the batch of boyish efforts that littered the editor's desk, and let my heart go out to the writers who were suffering the pangs that I had known so well.

I had had effusions of mine printed before that, but I didn't get any money for them. I had the pleasure of seeing my signature more than once in the columns of certain theatrical journals, in the days when I was a constant first-nighter, and a determined upholder of the privileges of the pit. And I even had some of my poetry printed. In the old box to which I have gone in search of the first edition of my first book, there are two papers carefully preserved, because they were once my pride and glory. One is a copy of the Halfpenny Journal, and the other is a copy of the Halfpenny Welcome Guest. On the back page of the correspondence column of the former there is a poem signed 'G. R. S.,' addressed to a young lady's initials in affectionately complimentary terms. Alas! I don't know what has become of that young lady. Probably she is married, and is the mother of a fine family of boys and girls, and has forgotten that I ever wrote verses in her honour. I think I sent her a copy of the Halfpenny Journal, but a few weeks after a coldness sprang up between us. She was behind the counter of a confectioner's shop in Camden Town, and I found her one afternoon giggling at a young friend of mine who used to buy his butterscotch there. My friend and I had words, but between myself and that fair confectioner 'the rest was silence.'

I was really very much distressed that my pride compelled me never again to cross the threshold of that establishment. There wasn't a confectioner's in all Camden Town that could come within measurable distance of it for strawberry ices.