This ill-treated tale was 'published' when I was ten, but an old schoolfellow recently wrote to me reminding me of an earlier novel written in an old account-book. Of this I have no recollection, but, as he says he wrote it day by day at my dictation, I suppose he ought to know. I am glad to find I had so early achieved the distinction of keeping an amanuensis.

The dignity of print I achieved not much later, contributing verses and virtuous essays to various juvenile organs. But it was not till I was eighteen that I achieved a printed first book. The story of this first book is peculiar; and, to tell it in approved story form, I must request the reader to come back two years with me.

One fine day, when I was sixteen, I was wandering about the Ramsgate sands looking for Toole. I did not really expect to see him, and I had no reason to believe he was in Ramsgate, but I thought if Providence were kind to him it might throw him in my way. I wanted to do him a good turn. I had written a three-act farcical comedy at the request of an amateur dramatic club. I had written out all the parts, and I think there were rehearsals. But the play was never produced. In the light of after knowledge I suspect some of those actors must have been of quite professional calibre. You understand, therefore, why my thoughts turned to Toole. But I could not find Toole. Instead, I found on the sands a page of a paper called Society. It is still running merrily at a penny, but at that time it had also a Saturday edition at threepence. On this page was a great prize-competition scheme, as well as details of a regular weekly competition. The competitions in those days were always literary and intellectual, but then popular education had not made such strides as to-day.

I sat down on the spot, and wrote something which took a prize in the weekly competition. This emboldened me to enter for the great stakes.

There were various events. I resolved to enter for two. One was a short novel, and the other a comedietta. The '5l. humorous story' competition I did not go in for; but when the last day of sending in MSS. for that had passed, I reproached myself with not having despatched one of my manuscripts. Modesty had prevented me sending in old work, as I felt assured it would stand no chance, but when it was too late I was annoyed with myself for having thrown away a possibility. After all I could have lost nothing. Then I discovered that I had mistaken the last date, and that there was still a day. In the joyful reaction I selected a story called 'Professor Grimmer,' and sent it in. Judge of my amazement when this got the prize (5l.), and was published in serial form running through three numbers of Society. Last year, at a Press dinner, I found myself next to Mr. Arthur Goddard, who told me he had acted as Competition Editor, and that quite a number of now well-known people had taken part in these admirable competitions. My painfully laboured novel only got honourable mention, and my comedietta was lost in the post.

But I was now at the height of literary fame, and success stimulated me to fresh work. I still marvel when I think of the amount of rubbish I turned out in my seventeenth and eighteenth years, in the scanty leisure of a harassed pupil-teacher at an elementary school, working hard in the evenings for a degree at the London University to boot. There was a fellow pupil-teacher (let us call him Y.) who believed in me, and who had a little money with which to back his belief. I was for starting a comic paper. The name was to be Grimaldi, and I was to write it all every week.

'But don't you think your invention would give way ultimately?' asked Y. It was the only time he ever doubted me.

'By that time I shall be able to afford a staff,' I replied triumphantly.

Y. was convinced. But before the comic paper was born, Y. had another happy thought. He suggested that if I wrote a Jewish story, we might make enough to finance the comic paper. I was quite willing. If he had suggested an epic, I should have written it.

So I wrote the story in four evenings (I always write in spurts), and within ten days from the inception of the idea the booklet was on sale in a coverless pamphlet form. The printing cost ten pounds. I paid five (the five I had won), Y. paid five, and we divided the profits. He has since not become a publisher.

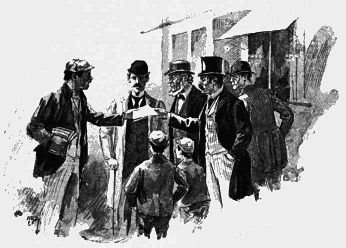

My first book (price one penny nett) went well. It was loudly denounced by those it described, and widely bought by them; it was hawked about the streets. One little shop in Whitechapel sold 400 copies. It was even on Smith's bookstalls. There was great curiosity among Jews to know the name of the writer. Owing to my anonymity, I was enabled to see those enjoying its perusal, who were afterwards to explain to me their horror and disgust at its illiteracy and vulgarity. By vulgarity vulgar Jews mean the reproduction of the Hebrew words with which the poor and the old-fashioned interlard their conversation. It is as if English-speaking Scotchmen and Irishmen should object to 'dialect' novels reproducing the idiom of their 'uncultured' countrymen. I do not possess a copy of my first book, but somehow or other I discovered the MS. when writing 'Children of the Ghetto.' The description of market-day in Jewry was transferred bodily from the MS. of my first book, and is now generally admired.

What the profits were I never knew, for they were invested in the second of our publications. Still jealously keeping the authorship secret, we published a long comic ballad which I had written on the model of 'Bab.' With this we determined to launch out in style, and so we had gorgeous advertisement posters printed in three colours, which were to be stuck about London to beautify that great dreary city. Y. saw the black-hair of Fortune almost within our grasp.

One morning our headmaster walked into my room with a portentously solemn air. I felt instinctively that the murder was out. But he only said, 'Where is Y.?' though the mere coupling of our names was ominous, for our publishing partnership was unknown. I replied, 'How should I know? In his room, I suppose.'

He gave me a peculiar sceptical glance.

'When did you last see Y.?' he said.

'Yesterday afternoon,' I replied wonderingly.

'And you don't know where he is now?'

'Haven't an idea—isn't he in school?'

'No,' he replied in low, awful tones.

'Where then?' I murmured.

'In prison!'

'In prison!' I gasped.

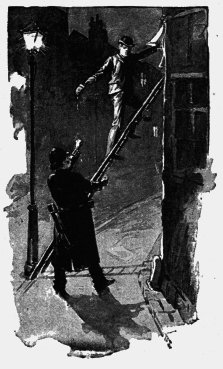

'In prison; I have just been to help bail him out.'

It transpired that Y. had suddenly been taken with a further happy thought. Contemplation of those gorgeous tricoloured posters had turned his brain, and, armed with an amateur paste-pot and a ladder, he had sallied forth at midnight to stick them about the silent streets, so as to cut down the publishing expenses. A policeman, observing him at work, had told him to get down, and Y., being legal-minded, had argued it out with the policeman de haut en bas from the top of his ladder. The outraged majesty of the law thereupon haled Y. off to the cells.