Naturally the cat was now out of the bag, and the fat in the fire.

To explain away the poster was beyond the ingenuity of even a professed fiction-monger.

Straightway the committee of the school was summoned in hot haste, and held debate upon the scandal of a pupil-teacher being guilty of originality. And one dread afternoon, when all Nature seemed to hold its breath, I was called down to interview a member of the committee. In his hand were copies of the obnoxious publications.

I approached the great person with beating heart. He had been kind to me in the past, singling me out, on account of some scholastic successes, for an annual vacation at the seaside. It has only just struck me, after all these years, that, if he had not done so, I should not have found the page of Society, and so not have perpetrated the deplorable compositions.

In the course of a bad quarter of an hour, he told me that the ballad was tolerable, though not to be endured; he admitted the metre was perfect, and there wasn't a single false rhyme. But the prose novelette was disgusting. 'It is such stuff,' said he, 'as little boys scribble upon walls.'

I said I could not see anything objectionable in it.

'Come now, confess you are ashamed of it,' he urged. 'You only wrote it to make money.'

'If you mean that I deliberately wrote low stuff to make money,' I replied calmly, 'it is untrue. There is nothing I am ashamed of. What you object to is simply realism.' I pointed out that Bret Harte had been as realistic; but they did not understand literature on that committee.

'Confess you are ashamed of yourself,' he reiterated, 'and we will look over it.'

'I am not,' I persisted, though I foresaw only too clearly that my summer's vacation was doomed if I told the truth. 'What is the use of saying I am?'

The headmaster uplifted his hands in horror. 'How, after all your kindness to him, he can contradict you—!' he cried.

'When I come to be your age,' I conceded to the member of the committee, 'it is possible I may look back on it with shame. At present I feel none.'

In the end I was given the alternative of expulsion or of publishing nothing which had not passed the censorship of the committee. After considerable hesitation I chose the latter.

This was a blessing in disguise; for, as I have never been able to endure the slightest arbitrary interference with my work, I simply abstained from publishing. Thus, although I still wrote—mainly sentimental verses—my nocturnal studies were less interrupted. Not till I had graduated, and was of age, did I return to my inky vomit. Then came my next first book—a real book at last.

In this also I had the collaboration of a fellow-teacher, Louis Cowen by name. This time my colleague was part-author. It was only gradually that I had been admitted to the privilege of communion with him, for he was my senior by five or six years, and a man of brilliant parts who had already won his spurs in journalism, and who enjoyed deservedly the reputation of an Admirable Crichton. What drew me to him was his mordant wit (to-day, alas! wasted on anonymous journalism! If he would only reconsider his indetermination, the reading public would be the richer!) Together we planned plays, novels, treatises on political economy, and contributions to philosophy. Those were the days of dreams.

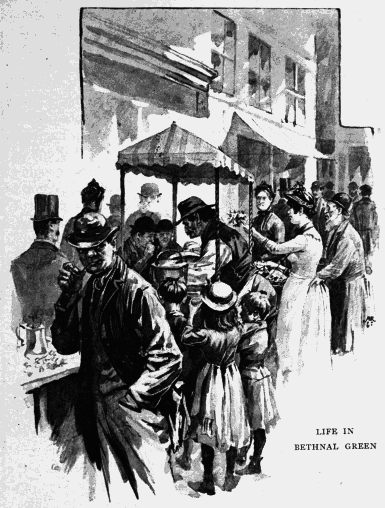

One afternoon he came to me with quivering sides, and told me that an idea for a little shilling book had occurred to him. It was that a Radical Prime Minister and a Conservative working man should change into each other by supernatural means, and the working man be confronted with the problem of governing, while the Prime Minister should be as comically out of place in the East End environment. He thought it would make a funny 'Arabian Nights' sort of burlesque. And so it would have done; but, unfortunately, I saw subtler possibilities of political satire in it, nothing less than a reductio ad absurdum of the whole system of Party Government. I insisted the story must be real, not supernatural, the Prime Minister must be a Tory, weary of office, and it must be an ultra-Radical atheistic artisan bearing a marvellous resemblance to him who directs (and with complete success) the Conservative Administration. To add to the mischief, owing to my collaborator's evenings being largely taken up by other work, seven-eighths of the book came to be written by me, though the leading ideas were, of course, threshed out and the whole revised in common, and thus it became a vent-hole for all the ferment of a youth of twenty-one, whose literary faculty had furthermore been pent up for years by the potential censorship of a committee. The book, instead of being a shilling skit, grew to a ten-and-sixpenny (for that was the unfortunate price of publication) political treatise of over sixty long chapters and 500 closely printed pages. I drew all the characters as seriously and complexly as if the fundamental conception were a matter of history; the outgoing Premier became an elaborate study of a nineteenth-century Hamlet; the Bethnal Green life amid which he came to live was presented with photographic fulness and my old trick of realism; the governmental man?uvres were described with infinite detail; numerous real personages were introduced under nominal disguises; and subsequent history was curiously anticipated in some of the Female Franchise and Home Rule episodes. Worst of all, so super-subtle was the satire, that it was never actually stated straight out that the Premier had changed places with the Radical working man, so that the door might be left open for satirically suggested alternative explanations of the metamorphosis in their characters; and as, moreover, the two men re-assumed their original roles for one night only with infinitely complex effects, many readers, otherwise unimpeachable, reached the end without any suspicion of the actual plot—and yet (on their own confession) enjoyed the book!

In contrast to all this elephantine waggery the half-dozen chapters near the commencement, in which my collaborator sketched the first adventures of the Radical working man in Downing Street, were light and sparkling, and I feel sure the shilling skit he originally meditated would have been a great success. We christened the book. 'The Premier and the Painter,' ourselves J. Freeman Bell, had it type-written, and sent it round to the publishers in two enormous quarto volumes. I had been working at it for more than a year every evening after the hellish torture of the day's teaching, and all day every holiday, but now I had a good rest while it was playing its boomerang prank of returning to me once a month. The only gleam of hope came from Bentleys, who wrote to say that they could not make up their minds to reject it; but they prevailed upon themselves to part with it at last, though not without asking to see Mr. Bell's next book. At last it was accepted by Spencer Blackett, and, though it had been refused by all the best houses, it failed. Failed in a material sense, that is; for there was plenty of praise in the papers, though at too long intervals to do us any good. The Athen?um has never spoken so well of anything I have done since. The late James Runciman (I learnt after his death that it was he) raved about it in various uninfluential organs. It even called forth a leader in the Family Herald(!), and there are odd people here and there, who know the secret of J. Freeman Bell, who declare that I. Zangwill will never do anything so good. There was a cheaper edition, but it did not sell much then, though now it is in its third edition, issued uniformly with my other books by Heinemann, and absolutely unrevised. But not only did 'The Premier and the Painter fail with the great public at first, it did not even help either of us one step up the ladder; never got us a letter of encouragement nor a stroke of work. I had to begin journalism at the very bottom and entirely unassisted, narrowly escaping canvassing for advertisements, for I had by this time thrown up my scholastic position, and had gone forth into the world penniless and without even a 'character,' branded as an Atheist (because I did not worship the Lord who presided over our committee) and a Revolutionary (because I refused to break the law of the land).