His severe judgment pronounced upon me, combined with similar, but perhaps milder, severity on the part of the other 'readers,' had, however, an unexpected result. Mr. George Bentley, moved by curiosity, and possibly by compassion for the impending fate of a young woman so 'sat upon' by his selected censors, decided to read my MS. himself. Happily for me, the consequence of his unprejudiced and impartial perusal was acceptance; and I still keep the kind and encouraging letter he wrote to me at the time, informing me of his decision, and stating the terms of his offer. These terms were, a sum down for one year's rights, the copyright of the work to remain my own entire property. I did not then understand what an advantage this retaining of my copyright in my own possession was to prove to me, financially speaking; but I am willing to do Mr. Bentley the full justice of supposing that he foresaw the success of the book; and that, therefore, his action in leaving me the sole owner of my then very small literary estate redounds very much to his credit, and is an evident proof amongst many of his manifest honour and integrity. Of course, the copyright of an unsuccessful book is valueless; but my 'Romance' was destined to prove a sound investment, though I never dreamed that it would be so. Glad of my chance of reaching the public with what I had to say, I gratefully closed with Mr. Bentley's proposal. He considered the title 'Lifted Up' as lacking attractiveness; it was therefore discarded, and Mr. Eric Mackay, the poet, gave the book its present name, 'A Romance of Two Worlds.'

Once published, the career of the 'Romance' became singular, and totally apart from that of any other so-called 'novel.' It only received four reviews, all brief and distinctly unfavourable. The one which appeared in the dignified Morning Post is a fair sample of the rest. I keep it by me preciously, because it serves as a wholesome tonic to my mind, and proves to me that when a leading journal can so 'review' a book, one need fear nothing from the literary knowledge, acumen, or discernment of reviewers. I quote it verbatim: 'Miss Corelli would have been better advised had she embodied her ridiculous ideas in a sixpenny pamphlet. The names of Heliobas and Zara are alone sufficient indications of the dulness of this book.' This was all. No explanation was vouchsafed as to why my ideas were 'ridiculous,' though such explanation was justly due; nor did the reviewer state why he (or she) found the 'names' of characters 'sufficient indications' of dulness, a curious discovery which I believe is unique. However, the so-called 'critique' did one good thing; it moved me to sincere laughter, and showed me what I might expect from the critical brethren in these days—days which can no longer boast of a Lord Macaulay, a brilliant, if bitter, Jeffrey, or a generous Sir Walter Scott.

To resume: the four 'notices' having been grudgingly bestowed, the Press 'dropped' the 'Romance,' considering, no doubt, that it was 'quashed,' and would die the usual death of 'women's novels,' as they are contemptuously called, in the prescribed year. But it did nothing of the sort. Ignored by the Press, it attracted the public. Letters concerning it and its theories began to pour in from strangers in all parts of the United Kingdom; and at the end of its twelvemonth's run in the circulating libraries Mr. Bentley brought it out in one volume in his 'Favorite' series. Then it started off at full gallop—the 'great majority' got at it, and, what is more, kept at it. It was 'pirated' in America; chosen out and liberally paid for by Baron Tauchnitz for the 'Tauchnitz' series; translated into various languages on the Continent, and became a topic of social discussion. A perfect ocean of correspondence flowed in upon me from India, Africa, Australia, and America, and at this very time I count through correspondence a host of friends in all parts of the world whom I do not suppose I shall ever see; friends who even carry their enthusiasm so far as to place their houses at my disposal for a year or two years—and surely the force of hospitality can no further go! With all these attentions, I began to find out the advantage my practical publisher had given me in the retaining of my copyright; my 'royalties' commenced, increased, and accumulated with every quarter, and at the present moment continue still to accumulate, so much so, that the 'Romance of Two Worlds' alone, apart from all my other works, is the source of a very pleasant income. And I have great satisfaction in knowing that its prolonged success is not due to any influence save that which is contained within itself. It certainly has not been helped on by the Press, for since I began my career six years ago, I have never had a word of open encouragement or kindness from any leading English critic. The only real 'reviews' I ever received worthy of the name appeared in the Spectator and the Literary World. The first was on my book 'Ardath: The Story of a Dead Self,' and in this the over-abundant praise in the beginning was all smothered by the unmitigated abuse at the end. The second in the Literary World was eminently generous; it dealt with my last book, 'The Soul of Lilith.' So taken aback was I with surprise at receiving an all-through kindly, as well as scholarly, criticism from any quarter of the Press, that, though I knew nothing about the Literary World, I wrote a letter of thanks to my unknown reviewer, begging the editor to forward it in the right direction. He did so, and my generous critic turned out to be—a woman—a literary woman, too, fighting a hard fight herself, who would have had an excuse to 'slate' me as an unrequired rival in literature had she so chosen, but who, instead of this easy course, adopted the more difficult path of justice and unselfishness.

After the 'Romance of Two Worlds' I wrote 'Vendetta;' then followed 'Thelma,' and then 'Ardath: The Story of a Dead Self,' which, among other purely personal rewards, brought me a charming autograph letter from the late Lord Tennyson, full of valuable encouragement. Then followed 'Wormwood: A Drama of Paris'—now in its fifth edition; 'Ardath' and 'Thelma' being in their seventh editions. My publishers seldom advertise the number of my editions, which is, I suppose, the reason why the continuous 'run' of the books escapes the Press comment of the 'great success' supposed to attend various other novels which only attain to third or fourth editions. 'The Soul of Lilith,' published only last year, ran through four editions in three-volume form; it is issued now in one volume by Messrs. Bentley, to whom, however, I have not offered any new work. A change of publishers is sometimes advisable; but I have a sincere personal liking for Mr. George Bentley, who is himself an author of distinct originality and ability, though his literary gifts are only known to his own private circle. His book of essays, entitled 'After Business,' is a delightful volume, full of point and brilliancy, two specially admirable papers being those on Villon and Carlyle, while it would be difficult to discover a more 'taking' prose bit than the concluding chapter, 'Under an Old Poplar.'

A very foolish and erroneous rumour has of late been circulated concerning me, asserting that I owe a great measure of my literary success to the kindly recognition and interest of the Queen. I take the present opportunity to clear up this perverse misunderstanding. My books have been running successfully through several editions for six years, and the much-commented-upon presentation of a complete set of them to Her Majesty took place only last year. If it were possible to regret the honour of the Queen's acceptance of these volumes, I should certainly have cause to do so, as the extraordinary spite and malice that has since been poured on my unoffending head has shown me a very bad side of human nature, which I am sorry to have seen. There is very little cause to envy me in this matter. I have but received the courteously formal thanks of the Queen and the Empress Frederick, conveyed through the medium of their ladies-in-waiting, for the special copies of the books their Majesties were pleased to admire; yet for this simple and quite ordinary honour I have been subjected to such forms of gratuitous abuse as I did not think possible to a 'just and noble' English Press. I have often wondered why I was not equally assailed when the Queen of Italy, not content with merely 'accepting' a copy of the 'Romance of Two Worlds,' sent me an autograph

7

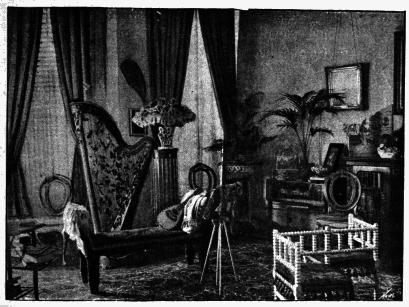

This and the succeeding illustrations are from photographs by 'Adrian.'