portrait of herself, accompanied by a charming letter, a souvenir which I value, not at all because the sender is a queen, but because she is a sweet and noble woman whose every action is marked by grace and unselfishness, and who has deservedly won the title given her by her people, 'the blessing of Italy.' I repeat, I owe nothing whatever of my popularity, such as it is, to any 'royal' notice or favour, though I am naturally glad to have been kindly recognised and encouraged by those 'throned powers' who command the nation's utmost love and loyalty. But my appeal for a hearing was first made to the great public, and the public responded; moreover, they do still respond with so much heartiness and goodwill, that I should be the most ungrateful scribbler that ever scribbled if I did not (despite Press 'drubbings' and the amusing total ignoring of my very existence by certain cliquey literary magazines) take up my courage in both hands, as the French say, and march steadily onward to such generous cheering and encouragement.

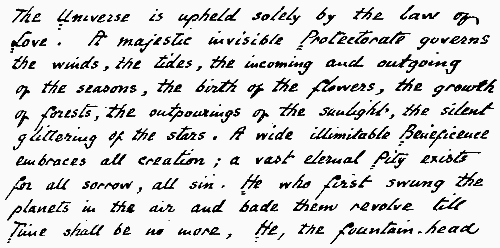

I am told by an eminent literary authority that critics are 'down upon me' because I write about the supernatural. I do not entirely believe the eminent literary authority, inasmuch as I have not always written about the supernatural. Neither 'Vendetta,' nor 'Thelma,' nor 'Wormwood' is supernatural. But, says the eminent literary authority, why write at all, at any time, about the supernatural? Why? Because I feel the existence of the supernatural, and feeling it, I must speak of it. I understand that the religion we profess to follow emanates from the supernatural. And I presume that churches exist for the solemn worship of the supernatural. Wherefore, if the supernatural be thus universally acknowledged as a guide for thought and morals, I fail to see why I, and as many others as choose to do so, should not write on the subject. An author has quite as much right to characterise angels and saints in his or her pages as a painter has to depict them on his canvas. And I do not keep my belief in the supernatural as a sort of special mood to be entered into on Sundays only; it accompanies me in my daily round, and helps me along in all my business. But I distinctly wish it to be understood that I am neither a 'Spiritualist' nor a 'Theosophist.' I am not a 'strong-minded' woman, with egotistical ideas of a 'mission.' I have no other supernatural belief than that which is taught by the Founder of our Faith, and this can never be shaken from me or 'sneered down.' If critics object to my dealing with this in my books, they are very welcome to do so; their objections will not turn me from what they are pleased to consider the error of my ways. I know that unrelieved naturalism and atheism are much more admired subjects with the critical faculty; but the public differ from this view. The public, being in the main healthy-minded and honest, do not care for positivism and pessimism. They like to believe in something better than themselves; they like to rest on the ennobling idea that there is a great loving Maker of this splendid Universe, and they have no lasting affection for any author whose tendency and teaching is to despise the hope of heaven, and 'reason away' the existence of God. It is very clever, no doubt, and very brilliant to deny the Creator; it is as if a monkey should, while being caged and fed by man, deny man's existence. Such a circumstance would make us laugh, of course; we should think it uncommonly 'smart' of the monkey. But we should not take his statement for a fact all the same.

Of the mechanical part of my work there is little to say. I write every day from ten in the morning till two in the afternoon, alone and undisturbed, save for the tinpot tinkling of unmusical neighbours' pianos, and the perpetual organ-grinding which is freely permitted to interfere ad libitum with the quiet and comfort of all the patient brain-workers who pay rent and taxes in this great and glorious metropolis. I generally scribble off the first rough draft of a story very rapidly in pencil; then I copy it out in pen and ink, chapter by chapter, with fastidious care, not only because I like a neat manuscript, but because I think everything that is worth doing at all is worth doing well; and I do not see why my publishers should have to pay for more printers' errors than the printers themselves make necessary. I find, too, that in the gradual process of copying by hand, the original draft, like a painter's first sketch, gets improved and enlarged. No one sees my manuscript before it goes to press, as I am now able to refuse to submit my work to the judgment of 'readers.' These worthies treated me roughly in the beginning, but they will never have the chance again. I correct my proofs myself, though I regret to say my instructions and revisions are not always followed. In my novel 'Wormwood' I corrected the French article 'le chose' to 'la chose' three times, but apparently the printers preferred their own French, for it is still 'le chose' in the 'Favorite' edition, and the error is stereotyped. In accordance with the arrangement made by Mr. George Bentley for my first book, I retain to myself sole possession of all my copyrights, and as all my novels are successes, the financial results are distinctly pleasing. America, of course, is always a thorn in the side of an author. The 'Romance,' 'Vendetta,' 'Thelma' and 'Ardath' were all 'pirated' over there before the passing of the American Copyright Act, it being apparently out of Messrs. Bentley & Son's line to make even an attempt to protect my rights. After the Act was passed, I was paid a sum for 'Wormwood,' and a larger sum for 'The Soul of Lilith,' but, as everyone knows, the usual honorarium offered by American publishers for the rights of a successful English novel are totally inadequate to the sales they are able to command. American critics, however, have been very good to me. They have at least read my books before starting to review them, which is a great thing. I have always kept my 'Tauchnitz' rights, and very pleasant have all my dealings been with the courteous and generous Baron. All wanderers on the Continent love the 'Tauchnitz' volumes—their neatness, handy form, and remarkably clear type give them precedence over every other foreign series. Baron Tauchnitz pays his authors excellently well, and takes a literary as well as commercial interest in their fortunes.

Perhaps one of the pleasantest things connected with my 'success' is the popularity I have won in many quarters of the Continent without any exertion on my own part. My name is as well known in Germany as anywhere, while in Sweden they have been good enough to elect me as one of their favourite authors, thanks to the admirable translations made of all my books by Miss Emilie Kullmann, of Stockholm, whose energy did not desert her even when she had so difficult a task to perform as the rendering of 'Ardath' into Swedish. In Italy and Spain 'Vendetta,' translated into the languages of those countries, is popular. Madame Emma Guarducci-Giaconi is the translator of 'Wormwood' into Italian, and her almost literal and perfect rendering has been running as the feuilleton in the Florentine journal, La Nazione, under the title 'L'Alcoolismo: Un Dramma di Parigi.' The 'Romance of Two Worlds' is to be had in Russian, so I am told; and it will shortly be published at Athens, rendered into modern Greek. While engaged in writing this article, I have received a letter asking for permission to translate this same 'Romance' into one of the dialects of North-west India, a request I shall very readily grant. In its Eastern dress the book will, I understand, be published at Lucknow. I may here state that I gain no financial advantage from these numerous translations, nor do I seek any. Sometimes the translators do not even ask my permission to translate, but content themselves with sending me a copy of the book when completed, without any word of explanation.