Он испуганно оглянулся, будто ожидая кого-то увидеть в мертвом хаосе, потом вспомнил: ведь это его собственные слова, сказанные вчера Гейслеру. Вчера? Или тысячу лет назад? Когда все это началось?

Мутный образ пятном выдвинулся из темноты… Он вгляделся: крысиная голова, неестественно большая, с оскалом зубов в разинутом рту. Он отмахнулся, — пятно потонуло во мраке. Кто-то вздохнул за спиною и тронул его влажной ладонью… Он закричал еще раз таким жалобным, совсем звериным криком. Потом мрак наполнился невнятными шорохами, вздохами, движением смутных контуров.

Теперь Гейслер говорил откуда-то из дальнего угла:

— Попробуйте поставить себя на место тех сотен тысяч, которых будут травить вашими газами…

И запекшиеся губы выдавили жалкий ответ:

— Да, это страшно — умирать…

Потом наступил хаос и забвение.

Только к вечеру следующего дня лаборатория была очищена от газов. В первой комнате нашли мертвую собаку в клетке. Вся кожа ее была покрыта волдырями и язвами, шерсть, висевшая клочьями, почернела и истлела. Морда была оскалена в судороге предсмертного воя.

Краны у баллонов с газом оказались отвернуты: служитель, заменявший старого Густава, исчез.

Розыски показали след его в направлении французской границы, гостеприимно открывшей свои объятия тому, кто впоследствии, при тщательном расследовании, оказался офицером французского генерального штаба.

В верхней комнате на столе, подле табурета, лежал человек с совершенно седыми волосами и выражением непередаваемого ужаса в остекленевших глазах. Тело его было нетронуто ожогами, кроме нижней части ног. Очевидно, он упал на стол после того, как движение облака прекратилось и газ осел вниз, просачиваясь в наружные щели.

В куче мусора, подле головы человека лежал молоток и пустая коробка из-под спичек. На полу, изуродованные ядом, в клочьях висящей шерсти валялись трупы двух крыс с вылезшими из впадин глазами.

Это было все. Штеккера хоронили через три дня с большой торжественностью. Говорились речи, центром которых была мучительная смерть на научном посту героя долга.

Гейслер слушал эти слова и думал упорно о своем, о том времени, когда безумие человечества останется в далеком прошлом и история развернет новую страницу, о которой сейчас мечтают и упрямые фантазеры, и люди крепкой воли, идущие к далекой, но неизбежной цели.

Приложение

The Revolt of the Atoms

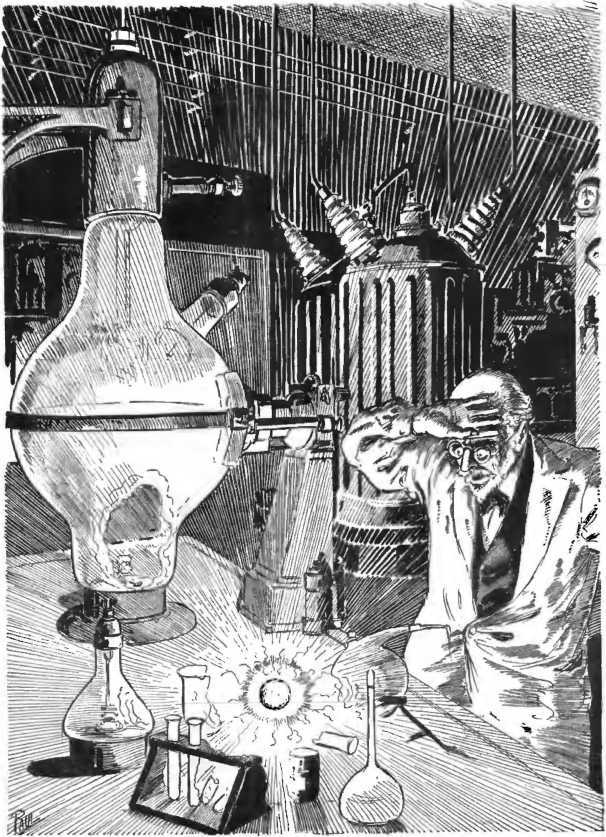

The present story comes to us from Russia and it is an extremely absorbing narrative based on excellent science. For the past decade, scientists predicted that if man ever harnessed atomic energy, things would probably begin to happen. They pointed out that the key to atomic energy was like the fulminate cap of a charge of dynamite. Dynamite is harmless and can be handled and sawed without danger. It requires the explosion of the little detonating fuse to set it off.

Scientists in the past have pointed out that if we discovered the key to atomic energy, we might very likely blow up the earth itself. A later school of scientists, however, disclaimed this entirely and they maintain that there is no such danger.

In any event, the present story is based on sound science and it makes exciting and interesting reading.

Indeed, there were reasons for it.

In the first place, this morning Flinder discovered, in his working cabinet adjoining the laboratory, the absence of several of his documents pertaining to his work. The theft had been committed at night with incredible and almost incomprehensible boldness. The laboratory was situated in the garden, in a separate building, in the rear of the large detached building in which he resided. The windows were protected with iron grating and from them radiated a net of wires connected with the burglar alarm system, not mentioning the special night-watchmen, old mon-commissioned officers. The result was that the wires were cut, the grating had apparently been cut through the comers with the oxy-hydrogen blowpipe, or something of that kind, and the window-panes had been cut out and removed.

The room was topsy-turvy. Two table-drawers Were pulled out and their contents were littered all over the floor. The thieves, it seemed, were pressed for time, for they had left the others undisturbed. But worst of all was the breaking open of the fireproof safe and the emptying of one of its compartments.

Something must have frightened the night intmders, pouting them into flight before they had succeeded in completing their work, for they left many traces behind: a handkerchief bespattered with dirt and ashes; drops of blood at the safe, apparently from excoriations on the hands; and scraps of newspapers of the preceding day. There were no tracks to be found in the garden. The Police Commissioner and a detective summoned by the professor, nodded their heads approvingly, inspected and examined everything, put what was of interest into their brief-cases, and left, to return shortly with a police dog. The hound jumped out through the window, leading his guides towards the stone wall, in which they found a large hole covered up with bushes. From there he led them into the garden and then into one of the crowded streets of Berlin. In a word, everything turned out to be just as it always happens in similar cases, but Flinder could not overcome the grief and excitement, even when the agents of the Police Department assured him that everything, so far, was progressing in their favor.

Having examined the remaining papers and documents, he discovered the absence of several which contained rough outlines of his recent work. Others embodied data which he kept secret, and which served him as connecting links for his future work.

He knew with certainty who stood behind this affair. It was quite clear that it was directed by one who knew his business thoroughly. For the past few years in Nancy, France, they were conducting experiments similar to his own. The little, dry, old man with that penetrating look in his deep-set eyes, gray tuft of hair on his forehead and sharp beard, whose photographs Flinder was examining with curiosity and animosity, in the “L'Illustration, directed this work and was stretching his avid and tenacious fingers in his direction. These two rivals had never met in their life, yet they hated each other with all the depth of feeling, of which each was capable in his own way.

Which of the two would be the first to harness this power and direct it by his own will, depended, to a great degree on the issue of the silent struggle between two nations, that struggle which, in fact has not ceased for a single moment, even after the cannon had ceased to roar and human flesh had ceased to be shot to pieces.

In to-day’s conflict, his opponent had the upper hand, a circumstance sufficient to spoil his best mood.

In addition, there was another unpleasant feature connected with this affair. Danger threatened from another side. For the past two years, a young Russian engineer commissioned here by Russia, had worked as a scientific collaborator in Flinder’s laboratory, commissioned by this amazing country, where only recently they had been feeding on human flesh and where people were dropping dead from hunger on the streets of the cities. This same country is now interested in electrification, in breaking up the atom, in the study of the nerve system and what not — which lines of work, according to Flinder, were not at all suited to savages and cannibals. At first, Deriugin, the Russian collaborator, displayed 110 qualities entitling him to any greater consideration than that given to his fellow-workers. In fact, he appeared rather to be possessed of a dull mind, or, at least, a mind not likely to lead him to the fore in this particular field. He worked along the lines of chemistry and radioactivity and, although this was in close contact with the research work of the professor, it never provoked any alarm in the latter’s mind.